FIRST TREATISE

LUMINOUS PHENOMENA AT THE POLES AND SIDES OF STRONG MAGNETS

The Magnetic light. The Aurora borealis.

- SENSITIVE persons, who are actually or apparently healthy, perceive nothing particular in the magnet beyond the excitement above mentioned, and bear the circuit of it without injurious influence. But this is not the case with the sick sensitive.1 The effect upon these is either pleasant, unpleasant, or fearfully adverse, according to the nature

of their disease; and the last sometimes to such a degree that fainting, cataleptic attacks, and cramps, arise of such violence that they may at last become dangerous. In the latter cases, among which somnambulists also are found, an extraordinary exaltation of the sensuous perceptions is usually met with; the sick smell and taste with uncommon delicacy and acuteness,—many kinds of food become as insufferable to them as the at other times most pleasant odours of flowers become disagreeable; they hear and understand what is spoken three or four rooms off, and are often so sensitive to light that, on the one hand, they cannot bear the light of the sun or of a fire, while, on the other, they are able, in great darkness, not only to perceive the outlines of objects, but to distinguish colours clearly, when the healthy can no longer perceive anything. These things are to a great extent well known, and require no further proof here. The intelligibility and possibility of them are by no means so far off as they appear, at first sight, to many who mistrust all such things as supernatural or incredible. Not only do most animals surpass civilized man in the delicacy of particular senses, but savages—therefore man himself—not unfrequently equal dogs and other animals in smell and hearing: as to sight, horses, cats, and owls are ready examples of capacity to see tolerably well with the optical apparatus in dark night.

- Through the kindness of a surgeon practising in Vienna, I was introduced, in March 1844, to one of his patients, the daughter of the tax-collector Nowotny, No. 471, Landstrasse, a young woman of 25 years of age, who had suffered for eight years from increasing pains in the head, and from these had fallen into cataleptic attacks, with alternate tonic and clonic spasms. In her all the exalted intensity of the senses had appeared, so that she could not bear sun or candle-light, saw her chamber as in a twilight in the darkness of night, and clearly distinguished the colours of all the furniture and clothes in it. On this patient the magnet acted with extraordinary violence in several ways, and she manifested the sensitive peculiarity, in every respect, in such a high degree, that she equalled the true somnambulists (which she herself, however, was not) in every particular relating to the acuteness of sensuous irritability.

At the sight of all this, and in recalling to mind that the northern light appeared to be nothing else but an electrical phenomenon produced through the terrestrial magnetism, the intimate nature of which is still inexplicable, in so far that no direct emanation of light from the magnet is known in physics, I came to the idea of making a trial whether a power of vision so exalted as that of Miss Nowotny might not perhaps perceive some phenomena of light on the magnet in perfect darkness. The possibility did not appear to me so very distant, and if it did actually present itself, the key to the explanation of the aurora borealis seemed in my hands.

- I allowed the father of the girl to make the first preparatory experiment in my absence. In order to profit by the greatest darkness, and the maximum dilatation of the

pupil, from the eye having been long accustomed to the total absence of light, I directed him to hold before the patient, in the middle of the night, the largest existing magnet, a nine-fold horse-shoe capable of supporting about ninety pounds of iron, with the armature removed. This was done, and on the following morning I was informed that the girl had really perceived a distinct continuous luminosity as long as the magnet was kept open, but that it disappeared every time the armature was placed on it.

To convince myself more completely, and study the matter more closely, I made preparations to undertake the experiment with modifications myself. I devoted the following night to this, and selected for it the period when the patient had just awakened from a cataleptic fit, and, consequently, was most excitable. The windows were covered with a superabundance of curtains, and the lighted candles removed from the room long before the termination of the spasms.

The magnet was placed upon a table about ten yards from the patient, with both poles directed toward the ceiling, and then freed from its armature. No one present could see in the least; but the girl beheld two luminous appearances, one at the extremity of each pole of the magnet. When this was closed by the application of the armature, they disappeared, and she saw nothing more; when it was opened again, the lights re-appeared. They seemed to be somewhat stronger at the moment of lifting up the armature, then to acquire a permanent condition, which was weaker. The fiery appearance was about equal in size at each pole, and without perceptible tendency to mutual connexion. Close upon the steel from which it streamed, it appeared to form a fiery vapour, and this was surrounded by a kind of glory of rays. But the rays were not at rest; they became shorter and longer without intermission, and exhibited a kind of darting rays and active scintillation, which the observer assured us was uncommonly beautiful. The whole appearance was more delicate and beautiful than that of common fire; the light was far purer, almost white, sometimes intermingled with iridescent colours, the whole resembling the light of the sun more than that of a fire. The distribution of the light in rays was not uniform; in the middle of the edges of the horse-shoe they were more crowded and brilliant than toward the corners, but at the corners they were collected in tufts, which projected further than the rest of the rays. I showed her a little electric spark, which she had never seen before, and had no conception of; she found it much more blue than the magnetic light. It left a peculiar lasting impression on the eye, which disappeared very slowly.The interest with which the subject necessarily inspired me, made me wish to multiply my observations, and to test them by repetition and by carrying them further out. The patient had already began to recover; her irritability diminished daily, and there was therefore no time to be lost. Two days after, I joined her relations in a resumption of the experiment. It proceeded exactly in the same way and with the same results. Allowing a day to elapse, we repeated the experiment in the first instance with a weaker magnet, without informing her of the alteration; the observer did not see the phenomenon in the same manner now as at first, but only perceived what she called two fiery threads.2 These were evidently the edges of the two poles of the magnet, which were all that her eyes could perceive of the weaker luminosity. When we then opened before her the stronger 90lbs. magnet, she at once recognised the former luminosity, of the form and colour already known. After another interval of several days, during which her convalescence had greatly advanced, we renewed the experiment; but the light no longer made its appearance, even with the large magnet. The patient saw it less distinctly than before, smaller and rather unsteady: often it seemed to sink, then to brighten up again; sometimes almost to disappear, and then after a short time to return again. On the following evening she perceived in the large magnet only the two luminous threads; and the night after, the phenomenon was so imperceptible to her vision that she beheld only two flashes, vanishing rapidly like lightning, which appeared and disappeared every time the armature was pulled off.

- So far Miss Maria Nowotny. Her rapidly increasing health had now so far lessened her sensitiveness that no further experiments were practicable, or productive of new results. I had every reason to consider her statement as true and exact, since she was an intelligent girl, and, for her station, well educated and sensible; at the same time, to give it certainty and scientific reality, it was indispensable to seek about for corroboration from other quarters. Through the present investigations I had become acquainted with an accomplished physician, Dr. Lippich, House Physician to the Hospital, Clinical Professor in Ordinary in the Vienna University, and by his kindness I was introduced to a patient lying under his treatment in the hospital. This was Miss Angelica Sturmann, nineteen years of age, daughter of an inspector of farms in Prague, suffering from tubercular affection of the lungs, and long subject to somnambulism in its slighter stages, with attacks of tetanus and cataleptic fits. The influence of the magnet displayed itself so powerfully in her, after a few experiments, that she far surpassed Miss Nowotny in sensitiveness. When I stood in the darkened ward, holding the 901b. magnet open at a distance of six paces from the feet of the patient, while Professor Lippich stood beside her, and she was previously perfectly conscious of what was going on around her, the patient ceased to answer. She fell into tetanic spasms and complete unconsciousness, from the action of the magnet, immediately I had pulled off the armature. This did not hold out a

very hopeful prospect of the results of my experiments; but they were not in vain.

After a while the girl came to herself again, and said that at the moment I removed the armature from the large magnet she had seen a flame flash over it, about the length of a small hand, and of a white colour mingled with red and blue. She had wished to look at it more closely, when suddenly the action of the opened magnet took away her consciousness. I had an intense desire to repeat the experiment, to obtain more exact information of the circumstances. The patient, also, was perfectly willing; but the physician considered it injurious to the complaint of his patient, and I was therefore forced to abandon any further investigation of the matter. At the same time, I had attained my principal aim: a confirmation of Miss Nowotny's statements respecting the luminosity over the magnet was obtained: it had now been seen by a second person suffering from quite a different disease, without any communication with the first.

- In another ward of the hospital, Dr. Lippich took me to a young lad of some eighteen years, a journeyman glover, suffering from intermittent spasms, produced by fright and ill usage. When I approached him with the magnet he at once spoke of fire and flames appearing before him, and which returned every time I removed the armature. But the lad was so uneducated that it would have been impossible to make any accurate experiments with him; and in the meantime I found more interesting opportunities of tracing out my subject in detail.

- Miss Maria Maix, 25 years old, daughter of a groom of the chambers in the Imperial Palaces, residing at No. 260 in the Kohlmarket, was the next person who was brought to me, through the kindness of her physician. He was treating her for a paralytic affection of the lower extremities, with occasional attacks of spasms. She was neither a somnambulist, nor did she talk in her sleep; she had never

experienced any attacks of insanity, and was in all respects a young woman of clear good sense. When a large magnet was opened before her in the night-time, which was often done, she always immediately beheld a luminosity over it, resting an the poles, about a hand's breadth in height. But when she was labouring under spasms, the phenomena increased most extraordinarily to her eyes. She then saw the magnetic light, which now appeared greatly increased in size, not merely on the poles, but also perceived rays of light flowing from all over the outer sides of the steel, weaker indeed than at the poles, but spread universally over the whole horse-shoe, which appeared as a bright light, and, as in the case of Miss Nowotny, left a dazzling brightness before her eyes, which would not disappear for a long time. We shall see the meaning and connection of all this. Meantime I had now obtained the fourth confirmation of the observation of the magnetic light. But by far the most remarkable and clearest of the observers was yet to come.

- This was Miss Barbara Reichel, 29 years old, stoutly made, daughter of a servant in the Imperial Palace at Laxemburg. When a child of seven years, she had fallen from the window of the second floor of her dwelling, and from that time forward had suffered from nervous attacks, which passed in some degree into true somnambulism, and into talking in her sleep, and wandering in her dreams. The complaint was intermittent, coming and going at long intervals. The girl had just recovered from a violent spasmodic attack, but still retained all the irritability of her sharpened power of vision. She was at the same time quite strong, clearly conscious, looking well, and, moreover, walked alone through all the bustle of the town, to visit her relations. I invited her to my house, and received visits from her as often as I wished, in order to make use of her extraordinary sensitiveness to the magnet, in investigations with

physical apparatus which could not well be taken to other houses.

This person united in herself the rare gifts, that she saw the magnetic light as strongly as any exhausted, helpless, sick patient, while she was outwardly healthy, active, and sensible, and that, with the greatest sensitiveness to the luminous appearances, she could bear the circuit of the magnet almost as well as a healthy person; which, with most of the sensitive, as we have an example of in Miss Sturmann, and as also occurred in a slight degree in Miss Nowotny, is so far from being the case, that an open magnet is liable to throw them into convulsions, and even render them senseless. Little can be done with such; but with Miss Reichel I could follow every investigation quietly to the end. Individuals like her are invaluable for scientific inquiries: and thus I have through her been able to obtain most valuable elucidations of the electromagnetic theory. In this place I shall in the first instance only indicate those observations which relate to the emission of light from magnets.

She saw the magnetic light not only in darkness, but in the dim light" which I required to perceive all objects, and thus manipulate, to modify, and repeat the experiments. If the obscurity was moderate, the magnetic light appeared shorter and smaller, she saw less of it; that is, those parts in which the light was weakest were first overpowered by day-light; but she saw the flaming effluences most brilliantly, their size greatest, their definition sharpest, and the play of colour most distinct, when the darkness was perfect.

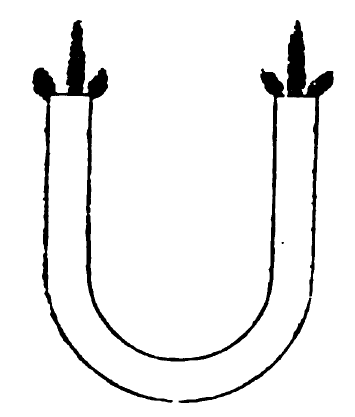

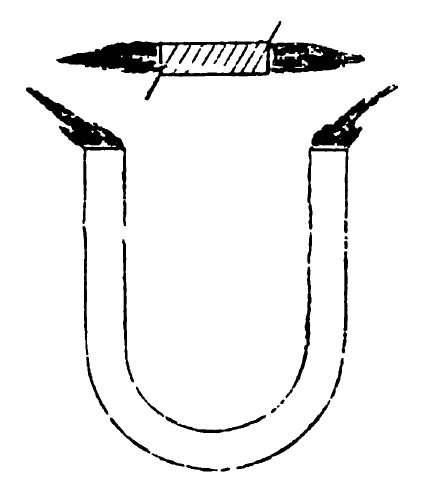

- When a magnet was laid before her in darkness, she saw it emit light, not merely when open, but when it was closed, like a horse-shoe, by the armature. This may at first sight appear surprising; but the sequel will show that this statement of the observer corresponds perfectly with the intimate nature of the matter. The two luminous pictures were naturally different in every respect. On the closed horse-shoe she could not detect any place at which the flaming appearances were especially concentrated, as they were at both poles when it was open; but the magnet emitted from all its edges, points of junction of the plates, and angles, a short flame-like luminosity, with a constant undulating motion. With a horse-shoe composed of nine layers, capable of supporting ninety pounds, this was not longer than about a finger's breadth.

-

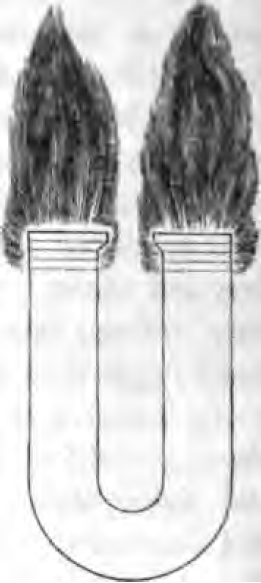

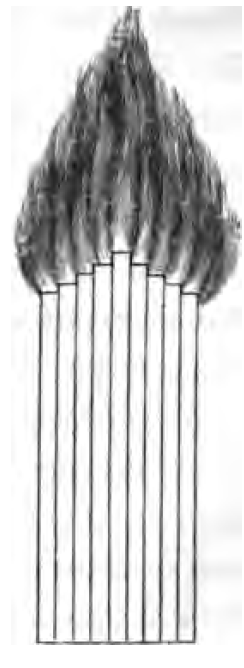

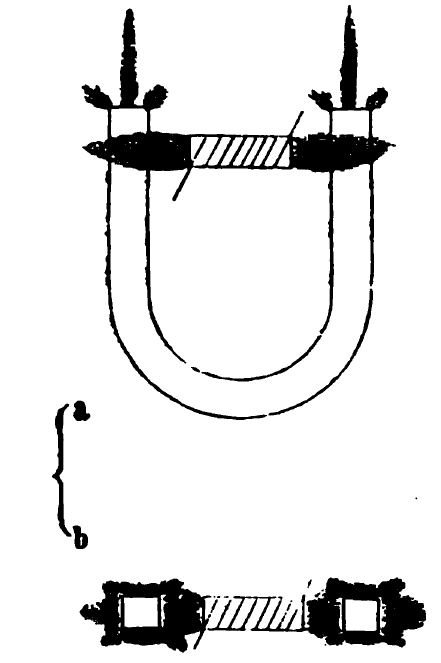

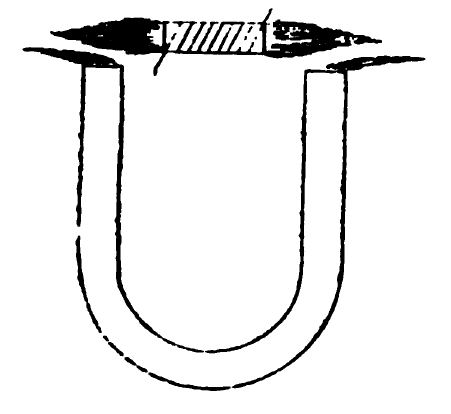

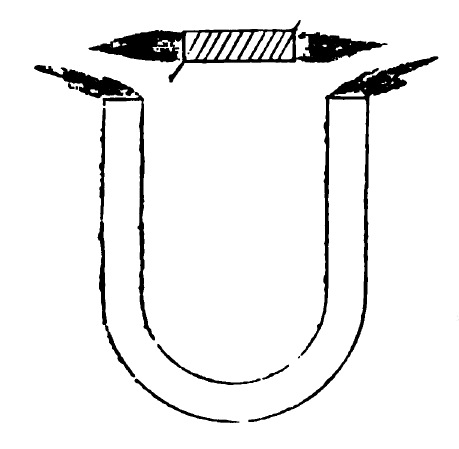

When the horse-shoe was opened, it exhibited the beautiful appearance represented in fig. 1. The drawing was prepared by Miss Reichel herself, as well as she could execute it; but she lamented that she was not able to attain an exact imitation of nature. While an arm of the horse-shoe measured ten inches, the flaming light reached up almost to an equal length, and arose of greater breadth than the steel. At every break formed by the layers of the magnet, smaller flames stood around the edges and angles, terminating in sparkling brushes. She described these little flames as blue, the main light as white below, becoming yellow above, passing then into red, and terminating at the top with green and blue. This light did not remain still, but flickered, waved and darted continually, so as to produce, as it were, shooting rays. But here also, as had occurred in the observation of Miss Nowotny, there was no attraction, no intermingling of the flames, not even an indication of a tendency to this, from pole to pole; and as there, too, no observable distinction between the condition of the two poles of the horse-shoe. Fig. 2 gives a side view, in which a separate tuft, of a lighter, flame-like appearance, spreads out from the edge of each component layer of the magnet This was necessarily omitted in fig. 1, for the sake of distinctness. Along the back and inner sides of the steel, weaker lights streamed out universally, like those which had been partially described by Miss Maix: on the inside they were all curved upward, but on the outside they were only turned upward for a short space, then were straight for a moment, and next took the directly opposite direction downwards. They were shortest at the lowest part, on the curvature of the steel; therefore on the magnetically indifferent space. These shorter weaker rays are very delicate, and also more fixed. They are drawn, from a single layer of steel, in fig. 10.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

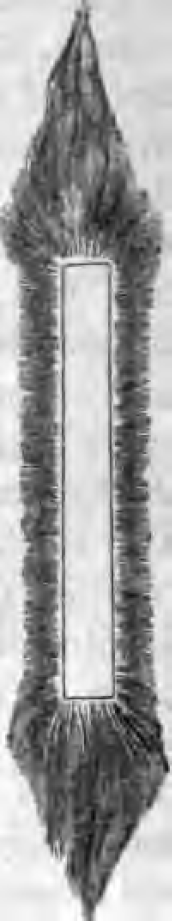

The condition of the luminosity along the four longitudinal edges of each of the nine layers of steel fitted upon one another, is worthy of remark. At places where the edges of two lamellae are accurately and closely fitted alongside one another, and almost form a continuous line, they were still clearly distinguished by the emission, on each side, of lines of flame, which one must suppose were necessarily confluent at the bottom. Directly above their point of origin they diverged, consequently converged toward the other lateral radiation of the same lamella; whence it follows, that a transverse section would exhibit such a figure as is represented in fig. 3.—Weaker magnets, from which Miss Reichel made drawings, gave the same picture, but the emitted rays were shorter.

Figure 10

-

I laid before her a straight magnetic rod. It was about 1½ feet long, quadrangular, and about 1½ inches broad, like common bar iron. She made from this the drawing subjoined in fig. 4. At the pole directed towards the north, therefore at the negative end of the magnet, she saw a large flame; at the opposite, positive end, a smaller, about half as large, waving, dancing, and shooting out rays, as in the horseshoe, red below, green in the middle, and blue above. From each of the four edges of either polar extremity issued a strong light, each independently flowing out at an angle of 45° to the plane of the base, and having a somewhat rotatory motion, not exhibited by the chief, central, flickering flame; thus there was a twofold distribution at each pole. A similarity exists in the statements of Miss Nowotny, who also perceived a stronger and more elongated flame at each solid angle of the horse-shoe. The four edges of the rod were clothed with a weaker light, just like the individual layers of the horseshoe; this exhibiting the red, green, and blue colours, but otherwise issuing steadily and without motion. It did not present any decrease along its whole extent, and neither edges nor indifferent points could be recognised, as was the case in the horseshoe.

Figure 4

-

Placing the magnetic bar in the meridian or in the magnetic parallel, with the poles directed forward or backward or in the direction of the dip, did not appear to exert any important influence in the shape or direction of the flames, the terrestrial magnetism not being strong enough to effect any considerable opposing action.

- I now took an electro-dynamic apparatus, on the one hand to make an electro-magnet before her eyes, on the

other to bring to observation the action which this and a common steel magnet would produce upon one another in reference to the luminous phenomena. It consisted of a horse-shoe magnet with the poles widely separated, between which a horizontal coiled electro-magnet could be made to rotate. The magnet itself, the poles of which were directed upwards, had legs of square section measuring about three-fourths of an inch on a side. In a dim light it exhibited a condition essentially similar in all respects to that which the large horse-shoe magnet had presented; at the four solid angles of the polar extremities obliquely ascending flames, but in the middle of them, issuing from the centre of the plane of the base, a longer, erect, ascending flame. But this latter was not a -dense fiery mass here, for it had assumed the shape of a thin, straight, and vertically erected needle; a modification of the condition which might depend on the relative strength of the magnet, on its size, or on other accessory circumstances of its form. It is possible that a very slight excavation, which had been drilled in the two ends of the steel, for the rotation of fine points fitting on to them, may have contributed to this. The luminous appearance was stationary in this form, and, with a slight difference in size, almost exactly the same at both poles. When I caused a current from a single pair of Grove's elements to pass through the stout silk-covered wire coiled round the iron which served for the electro-magnet, this emitted flaming lights from both ends, and exhibited in an instant all the luminous phenomena of a magnetic rod. Nay more; when it was removed out of the voltaic current, and had thus ceased to be a magnet, it continued to emit magnetic light from the poles, and, as regards luminosity, like the Ritter's pile, went on acting after the removal of the cause. (I shall return to the reason and explanation of this phenomenon in one of the succeeding treatises). Consequently, in the eyes of a sensitive person, an electro-magnet exhibits exactly the same behaviour in its emission of flaming light, as the common steel magnet.3

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 7 Figure 8

-

But the reciprocal action exerted by the two flames upon each other was remarkable. The flame of the steel magnet was completely turned aside by that of the electromagnet, and that as distinctly as the current of a blowpipe directs the flame of a candle. To shorten as much as possible the descriptions, which are tedious to read and at the same time difficult to comprehend, I briefly direct attention to figures 5, 6, 7, and 9. Fig. 5 represents the steel magnet with its luminosity alone, fig. 6, a and b, the electro-magnet underneath the poles of the latter, with the outline, fig. 7, beside it, fig. 8 close above it, fig. 9 high over it, and showing the remarkable divergence of the flame of the steel magnet. The question whether this is to be attributed to a difference of strength or to some other cause, is reserved for future investigation.

Figure 9

Thus in Miss Reichel we have the fifth and at the same time the clearest testimony for the luminous phenomena at the poles of the magnet. Lastly, I must mention a Miss Maria Atzmannsdorfer, a girl 26 years old (Golden Lamb, in the suburb Alte Wieden). She is the daughter of a pensioned military surgeon. She has an affection of the head, with spasms and sleep-walking; but walks about the streets looking like a healthy person. I brought her to my house late in the evening, when it was getting very dark, and into a room which I could darken perfectly by closing inside shutters. She was sensitive in a high degree, and saw the magnetic poles flame here in a most lively manner. She described the luminous appearance as still larger than Miss Reichel, from the nine-layered horse-shoe more than twice the height, and gave an exactly similar account of the light, the colours, and the mobility of the flame; like her she saw the whole magnet luminous, and its entire surface clothed with a delicate light. She makes the sixth witness.

- Let us now briefly compare the different statements: the same nine-layered horse-shoe magnet displayed at its poles, to the eyes of the greatly convalescent—

- Miss Nowotny, a kind of luminous vapour, surrounded and intermingled with rays of shining, moving, darting, white and sometimes iridescent light, about one half to three quarters of an inch long.

- Miss Maix, when free from spasms, saw a white flame about a hand's breadth high.

- Miss Sturrnann, a white flame as high as the length of a small hand, with an intermixture of colours.

- The journeymanglover, aflame a hand's length in height.

- Miss Maix, in a spasmodic state, a general light, distributed all over the magnet, dazzling her eyes, and issuing largest and strongest from the poles.

- Miss Reichel, a variously-coloured, Bickering, radiating flame, as large as the whole horse-shoe magnet, therefore 10 inches long; lateral flames out from each layer of the magnet; a general weaker efflux of light along all the edges of the layers inward over the whole horse-shoe.

- Miss Atzmansdorfer, the same appearances more strongly marked, and the entire magnet in a delicate glow.

- From all this it follows, that those sensitive persons, who are so in a high degree, perceive in the dark, at the poles of powerful magnets, a luminous appearance of a waving, flame-like nature, less or more according to the degree of their diseased sensibility, or the more or less perfect degree of darkness; that they do indeed differ in their observations as to its size, in consequence of their varying powers of perception, but agree unconditionally in all their general statements; such a luminous appearance of considerable magnitude, of which healthy persons see nothing, does therefore actually exist on magnets. Since, with the exception of an acquaintance between Miss Maix and Miss Reichel, none of the witnesses had any communication with each other, or did even know one another, but lived leagues apart, and in my innumerable experiments never contradicted one another, much less themselves; and since they never stated anything opposed to the fixed laws of electricity and magnetism; lastly, conscious of the precaution and accuracy of my own method of investigation,—I feel no hesitation in expressing the conviction I have arrived at,-- that I regard the reality of the perception, by persons of exalted sensibility, of luminous phenomena at the magnetic poles, as incontestible, and as an ascertained and settled fact of science; so far, that is, as an individual observer is in a position to complete it. I am certain that we shall not have to wait long for its confirmation from other quarters. The sensitive are not indeed so numerous in small towns, that they may be found almost everywhere, if sought; but in large cities they are far from rare, and I do not consider it a difficult task to find hundreds at once, if requisite, in a place like Vienna. My statements may therefore be readily tested in Berlin, Hamburgh, or Paris.

- We will now turn to some of the properties of the magnetic light. That it is invisible to healthy eyes, is not in itself very wonderful. When we consider the difference between sun-light and candle-light, the former of which Wollaston found 5560, Leslie even 12,000 times stronger than the latter; when we see how very weak is the luminosity of alcohol, wood-spirit, carbonic-oxide gas, pure hydrogen, and other combustibles, the flames of which are not only wholly invisible in strong sun-light, but become to a certain extent imperceptible in strong reflected daylight, we are aware already of such extreme differences between the luminosities of different flames, that the step to the complete invisibility to our eyes is no longer a great one, and hence the possibility as well as the comprehensibility lies tolerably near. It therefore cannot be regarded as strange, that other lights exist, which fall beneath our powers of vision, and that a luminosity pervades magnets, which, from its weakness, we are usually unable to see.

- To convince myself, where possible, whether it was actually light then, and not some different kind of appearance, that was perceived by the sensitive persons, I wished to make an experiment with the daguerreotype, and to see if an impression could be produced upon the iodized silver plate. To carry out this experiment, I invited my obliging friend, M. Karl Schuh, a private teacher of physics in Vienna, known by his improvements in the gas-microscope and his skill in daguerreotyping. He shut up an iodized plate, in front of which an open magnet was placed, in a dark box, and at the same time deposited another plate in another dark case, without a magnet. After some hours he found the former, when it had been treated with mercurial vapour, affected by light, the other not; but the distinction was not very strong. In order to make it perfectly clear, he took the magnet, turned towards an iodized plate, with extreme precautions for keeping out every trace of light during the manipulation, of which I was witness, and

placed it in a case in a thick bed, and left it there sixty-four hours. Taken out in darkness and exposed to mercurial vapour, the plate now exhibited the full effect of the light which it had received, over the entire surface. It was clear from this, that unless other causes are capable of affecting the photographic plate after considerable time, it, in fact, must be light, real, though weak and acting but slowly, which issues from the magnet.

- I made another experiment, with a similar view, with a large burning glass. The lens was about eight inches across, and had a focal distance of about twelve inches for a candle standing about five feet behind it. In a completely darkened room, I brought the magnet, of which the flame was ten inches long, about twenty-five inches behind the lens, and directed it against the wall, calling Miss Reichel's attention to it. The clever mechanist of this city, Mr. Ekling, was present. We removed the lens gradually four feet six inches from the wall, during which the observer saw the picture of the light continually diminish in size, and first at that distance contract to about one-eighth of an inch. But in spite of this, no one present was able to perceive a trace of the light, even under this considerable concentration. Yet it furnished us with a sure means of testing the accuracy of the observer in a variety of ways. Among others, she laid her finger on the spot where she saw the focal point; I followed her, and, by feeling in the dark, placed mine upon it. Mr. Ekling, who held the lens, now altered its direction a little, without saying in what way. The position of the focus on the wall was thus of course altered in the same direction. The observer immediately gave another, which I traced out with my finger, and then made Mr. Ekling state in what direction he had diverted the axis. Whether he said to the right, downward or upward, my finger was in every case already on the right, below or above. The exactitude and genuineness of the observationwas consequently beyond all doubt. She described the

colour the focal point as red; and she also said that the

whole of the large glass lens was illuminated red by the

magnet.

- The magnetic light emitted no heat; at least none appreciable by our most delicate instruments. Directed on to a Nobili's thermosoope, I could not detect any movement of the astatic needle of the differential galvanometer, even after a lengthened trial.

- It was very desirable to obtain some more intimate knowledge as to the substantiality of the flame, light, or whatever we may please to call it, waving over the magnetic poles. Since it did not issue in a radiant form from its source, but in a flickering shape, forming all sorts of curved and changing lines, it could not well consist of a simple and pure emission of light. In fact, when I turned the poles of the magnet downward, it flowed downward in the identical shape in which it flowed upward when I reversed them, and in each direction sideways as I held them to either side. This testifies strongly to its more than probable imponderability, but proves nothing positive as to its nature. But the answer I obtained to the question, how the magnetic flame behaved when blown upon, seemed to me more important in this respect. The observer said that it flared divergently to the side like any other flame. When a solid is brought too near, the points curl round it: when in the last experiments, also, the large glass lens had been brought too near the open magnet, the flames had applied themselves upon the glass exactly in the same manner as happens when another glass is placed in the flame of a candle to blacken it; when the hand was placed on the magnet, the flames passed between the fingers and out behind the hand, &c. It follows from this, that the magnetic flame is evidently either itself something wholly material, in or has such for a substratum; further, that the magnetic light is something different from it, and the magnetic flame is a compound, in which some kind of materiality is united with the immaterial essence of the light.4 The sensitive person actually sees the magnetic flame curve round the glass lens, while the light itself passes through, and its rays may be collected in a focus. Miss Nowotny and Miss Sturmann both assured me that the light spread a brightness around it, and illuminated neighbouring objects; and Miss Reichel marked the exact distance to which the visible light of the magnetic flame spread over the table on which it lay; I measured this, and found it to extend to about nineteen inches in diameter. Whether that which issues from the magnet in the form of flame is really a substantial emission, or only indicates an alteration of condition which the magnet produces in the surrounding air, or according to the newer theories, in the ether, which then in further progress becomes associated with an evolution of light, are questions to solve which many more things, among others the slow spontaneous loss of power of the steel magnet, must be placed in the balance, and they must remain as subjects for further research. For the present, only this much is established;—that the magnetic flame, turning aside before mechanical obstacles, is not identical with the independent, simultaneously issuing magnetic light, which possesses a higher radiant nature.

- And now I return to the introductory consideration of § 2. The first practical use to be made of these observations would be an endeavour to apply them to the elucidation of the aurora borealis. We are in possession of the valuable explanations given by Sir Humphry Davy, who applied the influence of the magnet on the electrical current in rarified air, to the aurora, and endeavoured to make out the probability that this phenomenon was produced by a current of this kind on the outermost limits of the atmosphere. But since, through the recent polar expeditions, it has been found how deeply this frequently descends in the atmosphere, Davy's ingenious comparison has lost much of

its certainty; the rarified space, the ground on which he based it, has disappeared, and with it the diffusion of the free electricity, which, derived from our thunder-storms, he claimed for the aurora. The certainty which we possess that the aurora is only formed under the influence of the magnetic poles of the earth, the total absence of any direct phenomena of light on magnets, which we have hitherto assumed; the facts now gained, that although invisible to common eyes, coloured, especially white, yellow, and red emissions of light do issue from magnets, certainly must lead us to surmise that the aurora may be either actually the magnetism itself issuing from the polar regions, or else a direct effect of it. It is known that the aurora, when it appears, affects and disturbs the magnetic needles of whole countries, as does the magnetic flame, or the magnet producing it, at a certain distance: lastly, it is, in fact, only the emanation from the magnet, and not the magnet itself, which produces the movements at a distance; and thus, therefore, the deflecting action of the aurora upon the needle completely agrees with those of the magnet. Finally, if we compare the special phenomena in the appearance of the magnetic light and the magnetic flame, with those of the aurora, the probability of such an assumption evidently increases. The aurora is known as a white arc, according to others as a white vapoury or cloud-like mass on the polar horizon, from which shoot out towards the equator flickering, brush-like, wandering rays, the lines of which have indeed a principal direction, but are not parallel to each other, nor straight, but appear curved slightly in various ways, and sometimes scintillate. Their colour changes from the white of the arc to bluish, emerald green, yellow, and above all, red, which light they then spread over whole zones. The same mobility of emitted rays, the same flickering flame running in curved lines, the same brilliant play of colour, the same reddening of illuminated objects, we find described in exactly the same way by the observers of the magnetic phenomena. The observations, it is true, do not agree perfectly with each other, but they coincide in all important points. The distinctions between them depend chiefly on the different size of the flaming objects, which is of minor importance; it is explicable by the different degrees of sensibility to the magnetic light of different observers. In particular, we see two different pictures of light appear in the eyes of Miss Maix, according as she was either in a quiet condition or in an attack of spasms: in the former case, a flame of only a hand's breadth rested on the poles; in the latter, not only had this much increased and become more brilliant, but the entire large horse-shoe was covered with gushes of light. In the same way we find with Miss Nowotny, that the apparent size of the magnetic light, in her observation, kept pace with her convalesence, and that the picture of it appeared to become smaller, from period to period, in the same proportion as her disease diminished, till at last it became wholly imperceptible to her senses. At one particular period she recognised a kind of luminous vapour immediately over the steel, which the far more sensitive Miss Reichel never saw; from this cloud of vapour she saw the tufts of light issue in the same way as the latter perceived the tufts of light from the corners of weaker magnets. This vaporous cloud, immediately upon the steel, resembled in a high degree the polar luminous arc of the aurora; and if Miss Reichel, as she stated, saw nothing of it, the reason certainly is, that in her sight, which perceived the far more flickering light and the flames ascending from the shorter layers of the magnet, the vaporous cloud was covered or eclipsed by these so that she could not possibly see them. It might be expected that, with the progress of her recovery, a period would ensue in which the flames of the sides of the layers would disappear, and then the vaporous cloud would be free to

her eyes, and would be seen as well by her as by Miss Nowotny.

It is this calm, bright, cloud-like appearance, however, which brings the resemblance to northern light to such a high degree of agreement, that one is involuntarily led to the acknowledgment of the complete identity of the aurora and the magnetic light. But I must not be misapprehended: I do not wish to say that I regard the identity of the two phenomena as proved; for between lights visible and invisible to healthy eyes lies a chasm which is not yet filled up, and cannot even be filled up by the hypothesis of a different intensity of the two phenomena: but I believe this much to be certain, and that I may venture to express it, that an astonishing analogy exists between the two; so great, that the identity of the magnetic flame and the aurora rises unmistakeably to a high degree of probability.

- RETROSPECT.

- A strong magnet exercises a peculiar action upon the senses of many healthy and sick persons; it is an agent upon the vital force.

- Those who manifest this sensibility in a high degree frequently exhibit a great exaltation of the acuteness of the senses, and are then in a condition to perceive light and flame-like appearances upon the magnet. The strength and distinctness of this perception increases with the sensibility of the observer and the obscurity of the place.

- The pole —M gives the larger, the + M the smaller flame, in the northern latitude of Vienna. Its form and colour change according as the magnet is open or closed,— a magnet made by touch, or an electro-magnet—free, or under the influence of other magnets.

- Positive and negative flames display no tendency to unite.

- The flame may be mechanically diverted in various directions, just like the flame of a fire.

- It emits a light which is red, that acts upon the daguerreotype, and may be concentrated by a glass lens, but is without perceptible heat.

- Magnetic flames and their light exhibit such complete resemblance to the aurora, that I believe myself compelled to consider the two as identical.

Notes:

- There are many persons in the category of the sick sensitive upon whom, in England, these experiments have been repeated, and they have not always exhibited the phenomena detailed. In affording a most willing and respectful testimony corroborative of the greatest part of the facts reported above, whenever I have had it in my power to repeat the experiments with strong magnets, I nevertheless believe it to be of importance that the class of the sick sensitive to whom these facts are applicable should be more strictly defined. I have no doubt that many of the individuals above described could be most easily mesmerised into sleep; and of those who would not readily sleep, some would probably, by repetitions of mesmeric passes, be rendered more favourable for the development of the phenomena which the Baron has

noted. The very impressionable conditions sometimes present without sicknessi or disease is not one of perfect health—certainly not usually of vigorous health; but there are many states of disease in which that impressionability not only does not exist, but in which a sensitiveness of some organs is present without any of others. If it be absolutely necessary to yield to party considerations for the sake of advancing truth by a side route; if it be requisite to assume, in order to meet the silly prejudices of the ignorant, that experiments of the nature described in the text are valueless unless they be performed upon persons awake, who happen to have "an extraordinary exaltation of the sensuous perceptions," then many of the very numerous corroborations here, of the facts established by the Baron von Reichenbach in Vienna, must be thrown aside. But I am inclined to contend for their value; and no one can read the review in the 4th volume of the Zoist, by Dr. Elliot-son, of the Abstract of the Baron von Reichenbach's Papers, by Professor Gregory, without being struck by the strong analogies adduced from mesmeric experience of the Baron's facts. When it becomes more known that the mesmeric condition is simply a state of nervous system, sometimes artificially produced, sometimes spontaneously present, of an " exalted sensuous" state, or the very reverse, and that at pleasure, in many individuals, can be produced those conditions which the Baron endeavours to indicate at pages 6, 7, 8, there will be no more hesitation in preparing a mesmeric test than the chemist now experiences in producing a litmus test. The truth is, that we are at all times, while life remains in us, in a mesmeric condition, each varying in degree; and without the agency of the mesmeric forces we neither think, nor move, nor have our being.

It is a want of sufficient reflection on the use of terms that leads us astray from clear ideas on the various conditions of the nervous system. Because the matter has not been studied as it ought to be, the Baron von Reichenbach deprecates experiments on subjects who have been mesmerised. Suppose, which is actually the case, that the same phenomena are offered to our observation in the persons who have been made, by artificial expedients, highly sensitive—very impressionable, the facts are really just as valuable as if they had been displayed in those naturally impressionable. The only question is as to the numbers of mankind readily influenced to exhibit phenomena which prove the existence of the Baron's new force. If all men could conduct investigations as logically, as clearly, as philosophically as the Baron, we should now have it in our power to arrange the characters of each condition of the nervous system in an unmistakeable category. They would easily be tabulated. They would present a very interesting series. I have attempted to sketch my meaning in Essays on Mesmeric Phenomena, and on the Theory of Sleep (Zoist, Vol. iv.) Whatever may hereafter prove to be the varieties of the states in which individuals may be, when aberrant from the condition of " perfect health"—a condition upon the definition of which physiologists as yet might not agree—it is clear, to those who have studied this matter, that the gradations in the series of the phenomena have some connection with attraction and repulsion. If I observe in a hospital a patient who, in result of an accident, has been deprived of a portion of the frontal or parietal bone of his skull, so that the brain is exposed, I shall find, what Boerhaave long ago found, that this viscus, during sleep, occupies less space than in the vigilant condition. The particles of brain-matter are approximated, and an attraction is active among them. If this patient be awake, and I apply very gentle pressure on the surface of the brain, I induce a tendency to sleep. If I increase the pressure, I occasion coma; I continue to increase, and the stertor accompanying coma may cease, but the nervous condition is one of tonic spasm. The simple paralysis goes on to a rigid condition of the muscles. Convulsions supervene when the surface of brain pressed upon is not extensive enough, because partial irritation is produced upon certain nerves. I have made these experiments on several human beings; but the fairest mode of obtaining accurate results is to expose the brain in a rabbit, cat, or dog. Tickle the brain with a soft brush, and clonic spasms ensue. The brain appears to swell out, it occupies more space under irritation, and is subjected to a repulsive agency among its particles. So that the state of sleep and of coma, quietude, paralysis, rigid tonic spasm, are degrees of a condition influenced to exist under attraction; the state of vigilance, restlessness, activity, agitation, clonic spasm, are varieties of a condition influenced by repulsion. In "perfect health," there is no extreme state of attraction or of repulsion. But if health be disturbed by some poison, the inconvenience produces an improper state of the balance between the attractive and repulsive forces; the brain and nerves influence a want of due balance in the arterial and venous systems. With arterial fulness there is inflammation; with venous fulness there is congestion. The degrees of variety in nervous phenomena dependent on these opposite states are very numerous; but still a law exists which we have yet to trace out. The varieties of those nervous phenomena called psychological, closely allied to the varieties of the conditions of the arterial and venous systems, fall particularly as subjects of inquiry into the province of the student in mesmerism and phrenology; and the satisfactory solution of many problems suggested by facts in the text of the Baron von Reichenbach can never be arrived at without arranging all the gradations of facts belonging to the nervous system, under a scale of which the extremes are the deep tonic, and the deep clonic spasms. Complicated as the human nervous system becomes by the many varieties in cerebral structure offered by varieties in development of size, delicacy, or coarseness, and other characters and relations of phrenological organs, there nevertheless exist certain salient pathognomonic signs by which to establish the distinctions on which logicians may reason with accuracy; and in time it will be found that the condition of sleep mixed up with the second consciousness usually accompanying the modified waking state (the sleep-waking of Elliotson) is no obstacle to the attainment of truth in such experiments as those instituted by the Baron von Reichenbach. Indeed, one is sometimes convinced, in reading his details of experiments, that, however strenuous he is to avoid the imputation of mesmerism, he is all the while describing facts occurring in what is commonly and vulgarly called the mesmeric state. Here is the mischief of the want of definite terms. Certain events occur in a condition of the nervous system accompanied by full vigilance, identical with those which take place in the condition of sleep-waking. The Baron is quite content with the fact in vigilance, but thinks that in sleep-waking unsatisfactory. Deeper reflection and further experience would convince him that in a vast majority of cases, as a testing meter, the state of sleep-waking is the more complete—the more delicate.

- In repeating these experiments with persons of great impressionability, I have not been so fortunate at any time as to witness in a wide-awake person any other phenomenon than the appearance of one or sometimes two fiery threads, said to have been seen, in a room perfectly darkened, emanating from the poles of a powerful horse-shoe magnet. Some ladies have clearly distinguished these beautiful bluish threads of light proceeding upwards to the height of a foot or more. Some have seen a hazy cloud at a little distance on each side, "like that of a wet moon." One gentleman saw a hazy light very distinctly; another something like a piece of red-hot iron wire, varying from six inches to a foot in length. These persons were brought into my dining-room, which had been previously darkened and prepared, without being informed of the purpose for which they were introduced.

Into the same room, and under the same conditions, I have introduced persons who instantly fell asleep, became clonically convulsed, and passed rapidly into the deeply rigid or tonic spasm, so that I have withdrawn them into another room while they have been as stiff as if they were frozen; and there I have gradually produced a relaxation of the muscular system, and complete wakefulness, by the application of unmagnetised iron to the nape of the neck and to the soles of the feet. Some individuals under these experiments wake up by the ordinary mesmeric manipulations, remaining fixed with tonic spasm until I applied the unmagnetised iron. In the same individuals, twelve in number, I have produced the same phenomena without the previous clonic spasm, by touching the nape of the neck with pure gold, or with platinum, or with rhodium, or with nickel, or with cobalt, or with antimony, or with bismuth. In every case, except in one (M. A. D.), I was always able to dissipate the spasm and awaken the patient by means of iron applied to the nape of the neck. In that one—the case will be well remembered by Mrs. Charles Lushington and by Dr. Thomas Mayo, who were present—I held a newly-cast disk of cobalt about two yards off, without the patient's knowledge, directed towards her back. She fell forward insensible upon Mrs. C. Lushington, who was talking toher. She was rigid and insensible. The pulse was for a time imperceptible. A current from a single-coil electro-dynamic apparatus, which happened to be in action, was passed from the pit of the stomach to the nape of the neck. Colour gradually returned to her cheek, and her pulse and breathing removed our alarm. She slept on that occasion fifty-six hours. A fortnight afterwards I was induced to repeat the experiment, and she slept forty-seven hours. If I endeavoured to awake her by mesmerism, I found her idiotic, and I restored her to the influence of deep sleep, out of which she always awoke spontaneously, much refreshed and improved in vigour. This experiment, repeated in this case very often, has been attended with beneficial results to the patient's health; but she now never sleeps under the cobalt influence more than three hours. I have performed many of the Baron's experiments with magnets of different numbers of layers and with various powers. When the subjects of the experiments remain in the sleep-waking state, they describe almost exactly what the Baron has stated as fact regarding Miss Nowotny, and his other cases.

For some remarkable experiments with a large apparatus thirty-three inches high, made of iron wire a quarter of an inch in diameter, coiled fifty-six times in a circumference of eight feet, I refer to page 137 of the 4th volume of the Zoist. This coil was of an oval form, so constructed in order to enable me to place it with ease over any individual seated in an arm-chair. By means of one, two, three, or four of Smee's elements, each ten inches by five, a more or less powerful current was established, enabling me to use a magnetic force adapted to different susceptibilities. For nearly six months daily, for two hours, a nervous, highly sensitive, and strumous young man, aged 17, who had been twelve or thirteen years lame from an ununited fracture of his right leg, used to sit within this coil urged by four pairs of Smee's plates. He never was sensible of any light or of any cloud. He was very somnolent, but became wide awake again on being removed from the magnetic influence. Under this treatment he became stronger, and the bones of his leg were united. Acupuncture was occasionally practised where the local appearance indicated the measure. If, when he came out of his cage, he went into the next apartment, where six or seven young women were waiting, he touched any of them, instantly sleep and rigidity supervened. Sometimes in sport he would touch every one of them, and leave them all in deep sleep. I have myself often obtained this same result in various persons, male and female, who, being of impressionable constitutions, have gone into a deep sleep upon my touching them, after having in another room, without their knowledge, rubbed my hands upon the poles of a powerful magnet. I have notes of three lads, of different ages, cured of epilepsy by mesmerism, who could be instantly put to sleep and rendered rigid in this manner. Dr. Elliot-son's celebrated case of cancer cured by mesmerism, became rigid on touching a magnet. I know three different females so susceptible of magnetic influence that they are made ill, being seized with painful spasms, if I bring a middle-sized magnet concealed in my coat pocket into the room. These persons do not know each other.

- I had five years ago a beautiful case of somnambulism, ins female, who could in her sleep see the light from the poles of magnets, exactly as in this case; even where the armature was applied, she saw lambent blue flames issuing from between the magnet and the armature, and between the plates of which the magnet was composed. Awake, she saw nothing; but on looking at the magnet a while, she fell asleep, and then saw the light again. If she touched the magnet, instantly a deep sleep and rigidity seized her. When I operated with an electromagnetic single coil apparatus, the same phenomena occurred as in the magnet. While the keeper or contact-breaker continued its action, she saw volumes of blue light and cloud emanating from the coil around the bobbin; if the circle were closed, the current still passing, she still saw a subdued light, but the grey cloud as before; and if in this state she touched the coil, instantly she became unconscious and rigid. From this it is manifest, that besides that force which can influence the galvanometer, some other agent powerfully influences the human system; and that certain individuals in the mesmeric sleep-waking are as good tests of the presence of this agent as any sensitive individuals in an analogous condition of nerves, who may happen to be awake. Since the time above mentioned, several of my somnambules, separated from one another, each ignorant of the purpose of the experiment, have been, at different times, introduced to a room where an electro-dynamic apparatus has been in action, and they have seen an emanation from the coil exactly as in the above case. Moreover, in corroboration of the fact noticed by the Baron, each of these persons has repeatedly been put to sleep by touching the helix, at various intervals, from one hour to two hours after the Smee's battery has been removed.

- In a logical work, the meaning of such words as material and immaterial should be strictly defined. The question relates not here to Theology, but to Natural Science. Great confusion of ideas must inevitably result from misapprehension of the accurate import of terms. If I understand the adjective material, it relates to matter—something. On the other hand, immaterial relates to immatter —nothing. Divisibility is infinite. The attenuation of any substance in space is bounded only by the opposition offered to its expansion by the pressure of other matter; otherwise its expansibility would be infinite. It is impossible to conceive of its annihilation—of its being reduced to nothing. Without clear ideas, logic is nothing—philosophy is nothing—reason is nothing—truth is nothing. Their provinces are in entity. It is absurd to speak of reasoning upon nothing. We cannot conceive of nothing. Our faculties have no relations to nothing. Being in themselves something, we can have no faith in nothing. Move for an instant from physics to theology. It is the atheist who believes in nothing. The believer in a God, clearer in his logic, confessing, in great humility, his perfect and complete inability to grasp the idea of nothing, can never measure? more than the attributes of an all-wise, all - just, all-holy, and all-powerful Being; still, cannot believe that being non-existent. He talks perhaps of that Being being immaterial. He does not for one moment mean constituted of nothing! He would be wiser to avoid the use of terms which have no meaning. . . . Real humility, which characterizes real philosophy, leads him to say—" I do not know, but in future I will not talk nonsense about immaterialism. I will not get angry, I will not dispute about what no imagination can conceive. A being must be something, although I may be quite ignorant of the nature of that thing." It is highly important that, in all considerations on those agencies which are sometimes designated as imponderable forms of matter, we should not use such terms as immaterial. The term can be used only when there is an absence of a clear idea, or a willingness to envelop the mind in hazy cloudy clothing.

It is a mistake to suppose that accurate definition is necessary only in metaphysics. All the phenomena relating to the subject of light may one day be proved to belong to the science of psychology; and the researches now presented to public notice may indeed be regarded as the commencement of very numerous investigations hereafter by men ofscience, which must establish the relations of light to the phen of the human mind. It is silly and idle to oppose to the progress of clear ideas the confused nonsense which pervades the brains of men who cannot help hating all new truths. Those who are really honest and sincere in their religious faith, need never fear the advance of science. A wise and just God, permitting the developments of truth, decrees that man cannot alter the laws which regulate Nature in her operations. The repulsive agencies of his brain may malignantly oppose the revelations of science, which are the revelations of God's will to man given out at progressively advancing periods of that time which is a fragment of Eternity; but they cannot overwhelm the truth, and are able to stay its progress only as the midge intercepts the progress of the sun's light for a moment. To our limited ken, all Nature's truths are material. Mathematics have enabled wondrous philosophers to calculate the speed at which light travels, and the admirable observations in paragraph 16 of the text are sufficient to prove that the materiality of all light, when man's ken shall be enlarged by science, may come to be easily established. I have known at least fifty persons who have seen a grey silvery, or a blue light emanating from my hand and fingers, when they have been wide awake. I have known a great many persons who having been put into mesmeric sleep have declared that they have seen blue light issuing in copious streams from my n eyes, when I have concentrated my thoughts in the acts of volition or study. This is so common, that as the investigations into mesmerism proceed, I know there must he thousands of corroborations of the fact, instead of hundreds, as at present. W I 11 any one venture to say that a force having relation to such a light is not a material power? The light proceeds from the brain of a person willing, and impinges on a sleeper—sent to sleep by a magnet —or by a crystal. The light is sent forth by the will of that person, and becomes a motive power, for the recipient sleeper moves and obeys the mandate received through the luminous agency. I have repeatedly performed an experiment under these circumstances, and the results have been as above stated. But though I have often willed persona awake as well as sleep-viakers, and even magnetic and crystallic-sleepers, to do my silent bidding, proving that the light from my brain is a motive power, I regard some other experiments on rare subjects to he still more conclusive as to the material agency of the light which emanates from the human brain. I have caused it to travel 72 miles, producing immediate effects. I have witnesses who can testify that I have repeatedly willed an individual to come to me when at the distance of nearly two miles. I have witnesses who can testify that a patient for some months required the force of the light emanating from my brain by the exertion of the will, to enable her to sleep at all, when she was at the distance of nearly two miles from me. Hundreds of persons have seen an individual made insensible and rigid by my imagining a circle round her. In her delirium, which made her muscles enormously powerful, she would occasionally master several persons. My will, impinging its light upon her, rendered her not only tractable for a time, but set her fast, for hours, in a deep sleep and rigid spasm. If I imagined a bar on the carpet, she could indicate with accuracy the position and limits of that bar. She described it as a bar of blue light on the carpet; and if she were desired to get up and pass over it, she became insensible, and fell on the floor like any inanimate object. Sometimes I have placed this bar of light across the threshold of a door, and it has been impossible for her to pass over it. The sight of the blue bar of light, placed by an effort of my will, even after many repetitions of the experiment, made her fall down insensible; and she has remained insensible to all external impressions, like a person dead asleep on the floor, until I have willed the bar to disappear. Hundreds of persons have seen me perform this experiment. On one occasion I left the bar for one hour and a half, and she remained quite unconscious, getting up instantly when I willed its disappearance. Though not a common, this has not been a solitary case illustrative of such a striking fact. Charpignon (Etudes Phys. sur le Magn. Anim. Paris, 1843) has proposed physical tests to establish the existence of the mesmeric fluid. One of them consisted in collecting the fluid from the ends of the finger into a glass tumbler, and then getting patients to inhale the air collected in that glass vessel. This put the individuals to sleep. Several persons have seen while awake the blue light proceeding from my fingers, and collecting in the glass. I have directed their attention to other objects, so that they could not be aware of my resuming hold of the glass I had left, and have been unawares put to sleep by my pouring the fluid on the back of their necks. On several occasions lately, I have sat in one room willing the mesmeric light into a wide-mouthed phial of a pint capacity, and have taken it into another room, where, pouring the substance on a patient's head, she has instantly fallen asleep. These experiments, performed with every precaution to avoid sources of fallacy, can succeed only in cases of most extreme susceptibility. Repeated occurrences of these facts, and, as they are easily reproduced, we shall have have accounts of many of them, will establish the conclusion that a force which is a material agent, attended by or constituting a coloured light, emanates from the brain of man, when he thinks—that his will can direct its impingement—and that it is a motive power.