SEVENTH TREATISE

DUALISM TN THE PHENOMENA

Dualism in the Odic phenomena. Warmth and cold. Magnets, Crystals, Plants, the Human body; their two halves; all polar. +Od and —Od. Variability of the odic intensity in time, in the human body.

216. THE polar opposition in magnets, the dualism in every crystalline form, the symmetrical and sexual opposition in all living organization, made me conceive, even at the beginning of the present researches, that something of the kind might prevail here. The first and most evident character of this was afforded by the constantly recurring sensations of heat and cold, of pleasure and discomfort, which healthy and sick sensitive persons imagined they felt from all material objects. I did not, indeed, find all these persons agreeing as to those sensations from the same substratum, but as to the quality of any, when once they had determined its place among the warm or cold materials, all the sensitive almost always persisted in their first opinion. There must, therefore, necessarily exist here objective causes in respect to the substance, and subjective causes referable to the form of disease, which determined the, on one hand, constant, on the other, inconstant statements. An attempt gradually to advance along the trace of warm and cold, in order to arrive, by further investigation, at a certain scientific truth, was consequently surrounded by difficulties of manifold and peculiar kinds. They were only to be overcome by patience.

217. The first question was: What does the expression warm signify in the mouth of the sensitive? What the term cold? All the objects which they thus designate are, in every case, of equal thermometrical temperature; these words, therefore, cannot mark anything real, but must indicate an apparent temperature, and the expression is therefore to be taken in a figurative sense; it signifies an effect upon the sense of feeling, which resembles that of heat and of cold, depending upon some unknown cause.

218. Miss Sturmann found both a flask of oxygen gas and a piece of sulphur hot; Miss Reichel found them both cold; and Miss Maix found both hot while lying in her hand, but diffusing a cold air around: in the collective idea of difference of temperature in relation to the temperature of the air, at each time they all agreed; but as to the determination of the degree I received very different accounts; from three observers three different statements, and all three kept constantly to the same statements at all times and in every repetition.

219. From this it clearly followed, that not only was the objective cause residing in the matter present in unequal degrees in different substances, but that unequal irritabilities existed in different diseases. These latter, again, could either establish merely quantitative distinctions, so _that a substance reacted more strongly or more weakly upon a patient, which would, however, over-excite another; or qualitative distinctions might exist where, in one disease, a particular substance had always a warm reaction, in another always cold.

220. To get nearer to the natural laws lying concealed here, the question required to be stated more simply; it would not do to begin with substances of different kinds, it must be attempted with those identical. I therefore returned to my rock crystal and selenite, in which I might hope to bring to observation, in one and the same example, the different temperatures which appeared to the sensitive to run through all nature, and from this point to carry out the comparisons. With Miss Nowotny, therefore, I took a selenite four inches long with a natural point, and drew it down over the inside of her hand from the wrist to the tip of the middle finger, near the skin, but without touching it, while she was in the north-south position. She felt a cool wind pass over, as if one had blown on her hand through a straw, as has already been mentioned in § 33. I then reversed the crystal, and took the same course over the hand with the opposite point of the crystal; she now experienced no cold, but a tepid warmth, which was, besides, disagreeable. A rock crystal, rather longer, carried down over the hand in the same way with both ends, gave the same results. Miss Sturmann felt the downward pass over the hand of one pole of a tourmaline, warm; of the other pole, cold. Iceland double spar acted upon her exactly in the same way.

221. Miss Atzmannsdorfer expressed herself in the same way: the above selenite, passed down over her right hand, gave coolness to her with the same end that had given it to Miss Nowotny. When I passed the same point down over her left hand, she felt it still cooler. Reversing the crystal, the pass down the right hand was warm, down the left unpleasantly tepid. I made the same experiment with Miss Reichel. I passed the same selenite over her hands. The same end which had caused coolness to the above different sensitive persons also produced coolness in the downward pass over her right hand; in like manner over the left also cool, but more strongly and more agreeably. When I reversed the crystal, and operated in the same way with the other end, she found the pass down over the right hand scarcely cool, on the left hand warm. She said, when passing downward, it seemed as if something was taken from her; when upwards, as if something was given. Miss Maix expressed herself just in the same manner in similar experiments.1

222. Similar accounts have been given at 33, 34, 35, in regard to M. Schuh and Professor Endlicher. In the meantime many other persons who have experienced the same sensations have given me permission to cite their testimony: M. Theodore Kotschy, Dr. Venzl, M. Voigtlander the optician, Mr. Incledon, M. Studer; the - joiner Tischler must also be named among the healthy sensitive. M. Kotschy, as well as Mr. lncledon, could only bear a few repetitions of the pass of the cold end of the large rock crystal from the head down over the body, as they then felt sensibly affected in the stomach, and I was compelled to desist.

223. Generally, therefore, did all the experiments and witnesses agree, that one pole of the crystals gave a cold, the other a warm pass. I say expressly, generally, since here and there single persons occur who cannot settle properly about cold and heat, fancying the same passes to feel sometimes cold, sometimes warm, varying between the two feelings in different dispositions, or only becoming certainly clear and consistent as to the quality of the sensation after repeated passes. But there are in all cases healthy or merely slightly indisposed persons; the properly highly sensitive are but seldom in doubt. Novices in the experiments are, in particular, less clear at first. The special cases, however, in which the decision between cold and warmth was variable in them, I shall discuss hereafter, and trace them back to definite clear cases.

224. When a dualism in the crystallized bodies had been substantiated both by these facts and through much of that which was detailed in the second of these treatises, a dualism which follows in an unmistakeable parallelism with that of crystallization itself, the questions arose, what is the nature of this dualism P Does it consist of a duplicity? Or does it correspond to a real presence and absence? Or is it like a positive and negative opposition? I acknowledge that I can as little give a definite answer to these, as we can find a certain intelligence of cold and heat, of + E and - E, of + M and - M, &c. I was obliged to be content, for the present state of matters, to make certain of a parallelism which I might perhaps hope to discover between Od and crystallization, magnetism and electricity.

225. We know, from what has gone before, that Od has much agreement with magnetism, leaving out of consideration the capacity of the latter to attract iron, to take a direction from the terrestrial magnetism, &c.; in particular, that it affects the sensitive exactly in the same way. When I passed a magnetic needle down over the hands of different highly sensitive persons, they received exactly the same sensations as from a crystal of selenite, calcareous spar, topaz, &c. As a rule, the northward pole, that is, the negative end of the needle, declared itself cool; the southward pole, the opposite positive end of it, warm. When a perfect agreement of certain poles of crystals with certain others of the magnet was thus brought to evidence, a right was acquired to conclude a similarity of cause, and to apply a similar nomenclature to those poles of crystals which exercised effects wholly homologous to determinate poles of the magnet, and were gifted with corresponding fundamental qualities; so that when + M agreed with Od, we could apply the term + Od, and in reverse in the same way -Od.2

226. In order to work this out, I first investigated, more minutely, the relations of the sensitive to the poles of the magnet. I placed a small magnetic rod in the hands of Miss Maix; it was about four times as long as the breadth

of her hand. I first made her place both fists close together in the middle of the rod, so that the latter passed through both, the northward pole being turned toward the left side. She experienced a moderate amount of disturbance from this. I then made her advance her two fists along the rod, the left toward the left, till it enclosed the northward pole; the right toward the right till it enclosed the southward pole, briefly, in such a manner that she had one pole in each fist. The effect of this alteration was very perceptible; she now experienced a very active disturbance through both arms, the breast, and head. When she removed one hand from the rod, the disturbance ceased suddenly; it returned and vanished alternately, as she alternately grasped and let go one pole, retaining the other in the other hand. The same occurred when she repeated the operation with the other pole. Therefore, there was a condition like a current, a kind of circuit, as was observed before on the occasion of the contact with both my hands, of which I have already given an account in the third of these treatises, 4 86. For the control of this, I repeated it with a large horse-shoe magnet, placing one of her hands upon each pole, the left upon the northward. She immediately became pained and oppressed in the breast, by the circuit which she felt through this from the arms; the head was involved and soon rendered giddy, and the patient was again reminded of the " ring-game" which she had spoken of in the former case, &c. The moment I let her take one hand away from the magnet, she felt at once ,the interruption of the circuit, and again breathed freely. Every repetition afforded a similar result. In both experiments, especially the latter, stronger one, it was requisite that the northward pole should lie in the left hand, the southward in the right, for the sensations to be in any degree supportable: when I reversed the poles the patient could not bear it; she again experienced the strange conflict within her, already described, and evinced so great

internal torment, that I was obliged to give up the experiment immediately. If I venture to assume the existence of a circuit here, like that of the galvanic current, I am obliged to conclude that it here flowed from the positive southward pole, through the right arm and upper part of the body toward the left side, and then through the left arm and hand down to the negative northward pole of the magnet. Then, the left hand of the patient corresponded to the southward pole, and her right hand to the northward pole of the magnetic needle: in other words, her left would be positive, her right negative, in relation to magnetism in the old unaltered sense of the terms, and the quality of the left hand would have to be indicated by + Od (here = + biod), and that of the right by - Od (here =- biod).

227. It will be remembered from 5 86, that when I had placed my right hand in her left, and my left in her right, a similar circuit was felt by the patient, which she was able to sustain; but that when I crossed my hands, so that the hands of the same name came together, namely my right in her right, and her left in my left, the often mentioned so-called struggle arose within her, which she could not sustain, since it was insufferably painful to her. From this it follows, that my male hands corresponded perfectly, in qualitative magnetic respects, with the female hands of Miss Maix, that my right took the place of the negative, northward pole, and my left of the positive, southward pole, and therefore they possessed magnetism, with positive and negative properties, in just the same order as those of the patient; consequently, that men and women are organized exactly with the same polarity in these points.3

228. After I had cleared this up, I placed the magnetic rod in the left hand of Miss Maix, in such a manner that it extended from the tip of the middle finger upwards to beyond the hand, and on to a part of the arm. The northward pole lay above upon the arm, the southward below on the tips of the fingers: thus all remained in its natural arrangement. When I reversed the rod, discomfort commenced; the so-called struggle began from the wrist to the fingers. I now pushed the magnetic rod up her sleeve, so that it lay upon her fore-arm. When I kept the arrangement such that the northward pole lay above at the elbow and the southward below at the wrist, the patient found its position in accordance with the natural conditions; when I reversed the rod, the disagreeable contest at once became felt again.

I repeat here the observation which I have already made in an earlier place, and which must not be left out of consideration in the critical examination of these phenomena, that the patient lay in the magnetic meridian; the head to the north, the feet to the south, and the face looking southward.

229. If, now, as all up to this point has testified, the same force and influence upon the living organism occurs in crystals as in the magnet, a simple crystal brought into the same circumstances as the magnetic rod ought to produce the same results. I placed a crystal of selenite between the two hands of the patient. It soon appeared, however, that it was anything rather than indifferent how it lay between the tips of the fingers of the two opposite hands. First, she soon felt out that the two most distant points of the rhombohedron were indeed part of an internal force of the crystal, but not the strongest, for there were two others in the direction of the short diagonal, which were much stronger, and coincided with the polar main axes. Neither were the poles of their axes alike, for she found one distinctly warmer, the other cooler, just as the patients had always found. When she now held the crystals between her two middle fingers, so that the cool pole lay on the left middle finger and the warm on the right, the condition of matters was in certain respects accordant; but when I reversed the crystal the often-mentioned discomfort appeared. The cool pole of the crystal, therefore, corresponded to the northward pole of the magnet.; the warm to the southward. When I placed the crystal in the patient's left hand, short as it was, for the main axis only measured four inches, it was by no means indifferent to her in what direction the axis lay. If the cool pole was directed upward toward the wrist, the warmer toward the fingers, the patient found it pleasant, but if I reversed the direction of the poles, the disturbance of the internal conflict commenced, even though over a small extent. Similar experiments with granite, staurolite, and heavy spar, furnished exactly the same results.

230. I should scarcely have ventured to lay so much weight upon these observations if I had made them upon Miss Maix alone. It might have been a peculiar, perhaps variable, result of disease. But I always obtained exactly the same effect in repetitions of it in very different conditions of disease. When I extended to Miss Nowotny, already far advanced in convalescence, one of my hands, she felt each singly, in exactly the same way as Miss Maix; and when I gave her both hands, she felt herself subjected, in like manner, to the sensation of a circuit, which she could not long sustain. Miss Atzmannsdorfer found my right hand warmish in her left, my left hot in her left; when I gave her both hands, she at once felt the circuit, which affected her whole body, and rendered her head giddy. But when I extended my crossed hands to her, I was not very successful, for the effect was so violent, that she began to lose consciousness, even in a few seconds, and I was obliged to pause. With Miss Reichel my right hand was never disagreeable in her left, but my right was painfully unpleasant in her right. She felt the two oppositely corresponding hands through the whole arms, and soon in the head, but not nearly so strongly and insupportably disagreeable as when I grasped her crossed hands. All this is in perfect agreement with what I have circumstantially detailed of Miss Maix.

231. Thus the law is evolved, that determinate poles of crystals and of living organized structures correspond to the poles of the magnet in relation to Od, that crystals have in this sense a clearly displayed north and south pole; that the cooler always corresponds to the north pole of the magnet, the warmer to its south pole, and finally that, of the human hands, the right corresponds in kind to the northward pole, the left to the southward, both in the male and female sex. Therefore + Od (here + crystallod, or + biod) presents itself equivalent to + M, and - M parallel to - Od, &c.

232. For the further confirmation of the facts here unfolded, I will include in my report some other similar conditions, which have presented themselves in healthy persons, in particular in M. Carl Schuh, the private physicist. A man of healthy, powerful aspect, thirty years of age, and of vividly sensitive temperament, he exhibited far more excitability by Od, than many other persons, so that he thus constituted a certain medium between unsensitive healthy persons and excitable nervous patients. He had hardly ever been ill, but when he over-applied himself to his labours, he sometimes suffered for some hours from headache. He vividly experienced the influence of all crystals; large magnets affected him distinctly, even at the distance of a yard. When I placed my right hand in his left, he felt a disagreeable effect., in a few minutes, in his head; and when I took his right hand with my left, the disorder increased rapidly; it rose in a few minutes from the temples towards the brows, and in half a minute produced a throbbing headache, which soon became almost insupportable, and remained for almost eight minutes after I had set his hands free, disappearing gradually and slowly; when I crossed my hands with him, as I had done with the highly sensitive, he found it exceedingly unpleasant. Starting from the later observations, namely, that the right and the left stand, in the relation to one another, of negative and positive, I proposed to him to use his own right and left hands instead of mine, and to place his hands one within the other, without the interposition of mine. To the no small astonishment of himself and the rest of the company, he found that his headache came on immediately and just as strongly as when I had given him my two hands; that it remitted and gradually disappeared when he separated his hands, but, every time, returned directly he folded them together again. His negative right on his positive left formed a kind of " element," if I may borrow this expression from galvanism; the arc was completed by the arms and body, and the polarization, or, if the word may be admitted for once in subsidium, the circuit commenced, and then acted upon the brain. Several months later, when we again came to speak on the subject, he told me that at no time does he dare to leave the hands together: since he has known the effects, the commencement of the disturbance at once reminds him to separate his hands whenever he accidentally brings them together. Other healthy sensitive persons exhibited inewholly similar results. M. Kotschy at once felt affected by my hands, and when I reached him both, he described the effect as a kind of circuit, which flowed from and to me, through the arms and chest. When I gave the two hands crossed, he represented his sensations as annoying painful shocks in the arms and head, almost in the same words as Miss Maix. But M. Kotschy never suffered from headache. Mr. Incledon received a quite unbearable headache from my two hands; especially, however, when they were given to him crossed.

233. We are now in a position to cast a retrospective glance over the most striking phenomena in all the sensitive; namely, that when lying on the back in bed, or in a similar position on a seat, they were of all directions least able to bear the west-easterly position. This is the position with the head to the west and the feet to the east, the face turned towards the east. In this position, the whole right side is turned towards the south, while the entire left is directed to the north; or in other words, the positive side of their bodies is turned towards the positive pole of the earth, and their negative to the negative. Equivalent, therefore hostile poles, are turned directly towards each other, and since these mutually repel each other, it becomes to some extent comprehensible why such a position must become so exceedingly injurious to the patients so highly sensitive in these points. In July, when Miss Nowotny endeavoured to go out again, she was utterly unable, even out of doors, to hear a walk from the west towards the east. It would be impossible to find more perfect confirmation of my preceding observations; and M. Schuh is no bedridden and obscure patient, but an active man known and seen by half Vienna and half Berlin.

234. I undertook a thorough control of the law obtained with Miss Reichel. It is known from the preceding treatise that I possessed series of simple substances and preparations, prepared by Miss Nowotny and Miss Maix, arranged by them according to the degree of discomfort they experienced from them. But in their graduated series, although they ran by regular degrees from the electro-chemically strongest substances to the weakest, no regard at all was had to their negative or positive relation in the electro-chemical series; only the quantity of their effect upon the sensitive had been taken note of, and not their quality. If, then, as had every appearance, the distinction between cold and warmth, in the feelings of the sensitive, be founded upon a distinction between negative and positive, in the same way as between the poles of magnets and of crystals, the above-mingled series should be capable of being divided into two halves, according to their difference of cold and warmth by those who felt this, one of which halves should comprise the negative, the other the positive substances. In this experiment I used the series of substances Miss Maix had formed as a basis, and made Miss Reichel bring this into two groups, according to cold and heat. I here give the result. The series proceeds from the greatest strength down to the least. The numbers denote the order in which they were originally placed in Miss Maix's series, before it had been divided into two by Miss Reichel.

| WARM | COLD | |||

| 2. | Potassium | 1. | Oxygen gas | |

| 3. | Caffeine | 4. | Sulphuric acid | |

| 5. | Purple of Cassius | 6. | Iodide of gold | |

| 7. | Brucia | 8. | Diamond | |

| 15. | Chromic acid | 9. | Chloride of gold | |

| 19. | Picarnarate of lime | 10. | Sulphur | |

| 21. | Bromide of silver | 11. | Bromine | |

| 22. | Iodide of silver | 12. | Tellurium | |

| 23. | Iodide of bismuth | 13. | Osmic acid | |

| 26. | Picamar | 14. | Selenite | |

| 27. | Atropine | 16. | Lunar caustic | |

| 28. | Acroleine | 17. | Orpiment | |

| 31. | Rhodium | 18. | Chloride of mercury | |

| 32. | Narcotine | 20. | Oxide of platinum | |

| 35. | Strychnine | 24. | Iodide of carbon | |

| 37. | Sesqui-oxide of lead | 25. | Iodide of mercury | |

| 38. | Alloxan | 29. | Iodine | |

| 40. | Picrotoxine | 30. | Telluric acid | |

| 41. | Ultramarine | 33. | Cyanide of mercury | |

| 43. | Mesite | 34. | Selenium | |

| 46. | Citronyle | 36. | Paracyanogen | |

| 47. | Draconine | 39. | Prussic acid | |

| 48. | Bismuth | 42. | Salphuret of potassium | |

| 52. | Creasote | 44. | Arsenic | |

| 53. | Potaas | 45. | Oxide of mercury | |

| 57. | Lithium | 49. | Iodide of lead | |

| 58. | Cantharadine | 50. | Chloride of cyanogen | |

| 61. | Cetine | 51. | Chloride of lime | |

| 64. | AEsculine | 54. | Oxide of copper | |

| 66. | Baryta | 55. | Cyanide of potassium | |

| 70. | Melamine | 56. | Sulphuret of calcium | |

| 74. | Grey pig iron | 59. | Sulphate of morphia | |

| 75. | Murexide | 60. | Bromide of potassium | |

| 76. | Protoxide of manganese | 62. | Cyanic acid | |

| 78. | Hydrate of oil of turpentine | 63. | Antimonic acid | |

| 79. | Cholesterin | 65. | Sulphuret of cyanogen | |

| 80. | Asparagine | 67. | Hydrate of baryta | |

| 82. | Hyoscyamine | 68. | Parabanic acid | |

| 85. | Alloxantine | 69. | Borax | |

| 88. | Caryophylline | 71. | Acetate of morphia | |

| 89. | Allantaine | 72. | Hydrochlorate of citronyle | |

| 90. | Sulphuret of ammonia | 73. | Phosphuret of nitrogen | |

| 91. | Lime | 77. | Oxide of cobalt | |

| 94. | Gold | 81. | Titanic acid | |

| 97. | Zinc | 83. | Uric acid | |

| 98. | Stearine | 84. | Neutral phosphate of lime | |

| 99. | Chromium | 86. | Chloride of carbon | |

| 101. | Osmium | 87. | Carbazotic acid | |

| 104. | Palladium | 92. | Phosphorus | |

| 107. | Mercury | 93. | Bichromate of potass | |

| 108. | Delphinine | 95. | Oxide of nickel | |

| 109. | Daturine | 96. | Alcohol | |

| 110. | Lead | 100. | Chloride of chromium | |

| 113. | Oleic acid | 102. | Albumen | |

| 116. | Cadmium | 103. | Ammoniochloride of platinum | |

| 117. | Sodium | 105. | Protoxide of chromium | |

| 118. | Antimony | 106. | Black lead | |

| 121. | Red lead | 111. | Oxide of silver | |

| 124. | Morphia | 112. | Common salt | |

| 125. | Bensamide | 114. | Molybdic acid | |

| 126. | Veratria | 115. | Iodide of potassium | |

| 127. | Indigo blue | 119. | Sulphate of iron | |

| 129. | Titanium | 120. | Nitric acid | |

| 132. | Naphthaline | 122. | Oxide of manganese | |

| 133. | Coal wax | 123. | Sebacic acid | |

| 137. | Nickel | 128. | Stearic acid | |

| 138. | Copper | 130. | Massicot | |

| 139. | Santonine | 131. | Oxamide | |

| 140. | Iridium | 134. | Cinchonine | |

| 141. | Tin | 135. | Melan. | |

| 142. | Cobalt | 136. | Hippuric acid | |

| 148. | Amygdaline | 143. | Fumaric acid | |

| 149. | Malone | 144. | Malic acid | |

| 150. | Quinine | 145 | Benzoic acid | |

| 151. | Piperine | 146. | Lactic acid | |

| 156. | Benzoyle | 147. | Cinnamonic acid | |

| 157. | Urea | 152. | Peroxide of lead | |

| 158. | Platinum | 153. | Gallic acid | |

| 159. | Silver | 154. | Tannic acid | |

| 163. | Eupion | 155. | Succinic acid | |

| 167. | Bar-iron | 160. | Spring water | |

| 171. | Paraffine | 161. | Mannite | |

| 162. | Charcoal | |||

| 164. | Starch | |||

| 165. | Gum | |||

| 166. | Sugar | |||

| 168. | Vinegar | |||

| 169. | Sugar of milk | |||

| 170. | Citric acid | |||

| 172. | Distilled water | |||

235. When this arrangement is examined, it is seen that almost all metals, potassium at the head, with the isolated exceptions of tellurium and arsenic, are on the side of the warm bodies,-therefore, on the especially negative: we find, further, under this head, almost all organic substances, and organic bases; the compounds of carbon, rich in hydrogen, and barely a couple of acids, chromic and oleic. On the other hand, we observe in the opposite, cold side, all bodies like sulphur, bromine, iodine, selenium, all compounds of chlorine, the oxides of the metals, all compounds of cyanogen, and almost the whole of the acids. So far as we can judge of the substances, we perceive on the warm side scarcely anything but electro-positive--on the cold side, scarcely anything but electro-negative. It is certainly surprising, and in the highest degree worthy of notice, that a human being-a girl perfectly ignorant of such things-is capable of classifying with certainty and accuracy, according to one of their innermost, profoundest, and most obscure peenliarities-their electro-chemical character, all the substances of this world, without seeing them, and by mere dull sensation.

236. As we have been compelled to infer of the magnet, crystals, and human hands, all warmth giving substances are positive, so are we now obliged to conclude that all positive bodies give out heat. This holds good in the reversed formula of the negative, and thus we arrive, in a different way from that already known, at the electro-chemical series of bodies, which, from this point of view, we may call the Od-chemical series.

237. As to the manner and circumstances by which I obtained this result, I may add, that I gave the observer all the bodies which consisted of solid substance, into her bare left hand; the pulverulent on a fine, very thin tissue paper, which did not require to be taken into account; and the fluid in the bottles in which I usually kept them. I did not neglect to control this operation repeatedly, and most minutely, by making the same trials over again, in modified ways. At one time I placed all the bodies at one end of a long and wide glass tube, while Miss Reichel grasped the other in her whole hand. When I inserted one body after another into the tube, the feeling of warmth and cold changed in a moment. Another time, I selected a glass rod of such condition that it was not felt either warm or cold. With this I let her touch the substance, inserting it into the powders and fluids, and placing it against the side of the solids. With this kind of feeler she very accurately distinguished the warm or cold condition of bodies every time; and I can, from experience, especially recommend this mode of testing, as readily provided for, everywhere applicable, and very clear to the observer. By means of two such rods of equal thickness very accurate comparisons between two different bodies could be made. The examination of bodies, by placing them, together with the bottles in which they are contained, in the hands of the patients, is only possible with substances of great strength; as with sulphuric acid, potass, caffeine, &c. In the weaker, it is inadmissible, because the glass itself has very different properties, feeling, according to its chemical condition of admixture, sometimes warm, sometimes cold, and sometimes indifferent, and thus readily rendering the result incorrect. This frequently goes so far, that weak substances, which by themselves feel cool, are thereby made to feel warm, and vice verso; and then errors will be produced. Salts and other preparations, which occur in a crystalline condition, must be powdered before testing, even if only coarsely. For, since the crystals are polar, no pure result of quantity can be obtained from a group, as isolated crystals affect the result by their poles, and render it complex. I hesitated a long time, for instance, with saltpetre and bichromate of potass, between warm and cold, until I powdered them, when a constant coolness presented itself. And when a substance is powdered, it must not be examined immediately, but after some hours. For, the mortar and pestle in which it has been powdered influence it for a long time, through transference: in like manner, the rubbing in the trituration alters the natural odic value, since it brings in accumulation from friction, perhaps also from electricity, that may be thereby set in motion. Finally, the substances to be examined must not be allowed to remain previously for any time near other, especially much stronger or much weaker ones, because they will, in that case, become altered by transference; moreover, they must not have stood in the sunshine, nor in the moon's rays; they must not have remained long in the hand; when several are to be compared together they must be tolerably equal in temperature, &c. All these things would interfere with the purity of the result, as is abundantly evident from the preceding treatise.

238. I need scarcely observe that the series which I have above given is not to serve as the normal, but only as an example, and as a help to the argument. For to have been laid down as the type, it would have required the previous most accurate investigation of the chemical purity of the substances, a labour for which neither time nor circumstances have yet afforded sufficient opportunity. I merely intended to seek out and lay down the law; its accurate application will belong to another time. Countless other preliminary investigations are also requisite here, the infinity of which I fully feel and recognize; in the first place of all, these testings of positive and negative character of bodies, which I was here first able to carry through with Miss Reichel, must be undertaken with several other sensitive persons in different conditions; thereby must be found the key to the distinction of their sensations, as also the results of more exalted or lower excitability, in comparison with Miss Reichel, who, since her sensations coincided so accurately with the general electric condition of bodies, as it has been made out previously in other ways by physics and chemistry, must have been in a remarkable equilibrium,-one might say, of purity of diseased condition.

239. We will now make some applications of the discovered law, that substances which affect the sensitive as warm or cool, the thus od-positive or od-negative, correspond to the electro-positive and electro-negative. First of all, we found the sun strikingly cool, but the moon strongly warm on the sensitive; the fixed stars ranged themselves with the sun, the planets with the moon. I do not know whether astronomers have yet made out anything positive on this subject; so far as my knowledge goes, nothing has been made known on this point, except what M. Kreil4 traced into the qualities of the moon, from the interference with the declination of the magnetic needle. It is then certainly in some degree interesting, that the human feelings should be able to carry us so far as to recognize that the fixed stars take their place all on the electro-negative, the moon and the planets on the electro-positive side: luminous and illuminated stars are thus opposed in a polar manner to each other. Perhaps we shall one day succeed, if not in deciding, yet in raising a probability, that a comet which only sends us polarized light is actually a reflecting and not an illuminating body. Subjecting this to rigid criticism, it may indeed be objected that the feelings do not necessarily point here to the electro-chemical condition of the heavenly bodies, but only the influence of their emanations; their rays of light, of heat, &c. are perceived in the feelings of the patient. I do not at all oppose this; at the same time, all that we have yet succeeded in discovering about the heavenly bodies is perceived through emanations of each kind, by means of our senses; all that we know of them relates to that alone which arrives to us through their emissions, and thus we are in the same position with the odic emanations, which tell us that the sun is od-negative, and the moon od-positive, as the emanations of light teach us that the sun is warm, the moon almost without heat, &c.

240. From § 147, in the examination of the chemical activity, we already know that all fire effects the feelings of the sensitive with cold. This is so far worthy of regard, that we know from the researches of Pouillet (Annal. de Phys. et de Chim., tom. xxxv., p. 402), that the exterior of flames, which depend upon oxygen combinations, possesses much free positive electricity. This cold is not only diffused from the free fire of od-positive or od-negative bodies,- as from potassium, stearine, oil, alcohol, and sulphur, but it may also be detected when the fire is inclosed, whether it be in positive or negative bodies. For when Miss Reichel approached a stove warmed by the fire inclosed in it, she found it indeed warm at the greatest proximity, so long as its real heat acted in a preponderating degree upon her, especially with iron stoves; but when she drew back, scarcely a couple of steps, it caused her vivid sensations of coolness, and the stronger the more actively the fire burnt in the stove. When she was chilled in the winter time, and went to warm herself at the heated iron, it now chilled her through and through, and her fingers, which previously were rather stiff, became perfectly so; she was compelled to go away, and endeavour to warm herself by walking up and down the room and rubbing her hands. It was pretty nearly the same thing whether the stove was of earthenware or of iron. In judging this strange effect, it must not be overlooked what a complex phenomenon this is of what is given out by heat, light, chemism, the electricity thereby excited, the substance of the burning materials, and, finally, of the stove itself. The resultant, however, of all these components is, in all the cases hitherto observed, an uncommon degree of cold to a distance of many paces, so that it drove Miss Maix out of the illuminated churches, § 131, and Miss Reichel, when she remained only a short time in the vicinity of a burning wood fire, was in rapid succession first attacked in the head, then rendered giddy, and at last felt so seized with pain in the stomach that unless she hurried away she fainted. Fire, therefore, acts od-negativtly on the sensitive in all cases.

241. The question suggests itself here, what apparent temperature may be shown by flames of that kind which the 0(1 itself produces, and which, invisible to healthy persons, are perceived by the sensitive on the polar ends of wires from all the various sources of Od. To solve this I inserted first a glass rod, which itself felt cool, and an iron one, which felt warm, in a number of substances, and let Miss Reichel feel the flames issuing from the extremities at a distance of two inches. I obtained the following series, exactly similar, from the glass and iron rods:-

| COLD OD-FLAMES | WARM OD-FLAMES | |||

| Bichromate of potass. | Gold | |||

| Sugar | Platinum | |||

| Sugar of milk | Potass. | |||

| Citric acid | Narcotine | |||

| Oxalic acid | Minium | |||

| Chloride of lime | Oxide of lead | |||

| Sulphur | Cast iron | |||

| Bromine | Paraffine | |||

| Graphite | Mercury | |||

| Charcoal | Tin | |||

| Arsenic | Cadmium | |||

| Manganese | Iridium | |||

| Alcohol | Creosote | |||

| Sulphate of iron | Iron-filings | |||

The apparent temperature of the flames agreed accurately, therefore, with the temperature which the substances, on which they depended, had shown, by feeling in immediate contact, by feeling through a long glass-tube, and with a glass rod: all od-negative substances give cold, all od-positive warm flames. The temperature of the flames, therefore, affords an expression of the odic quality of bodies in general.

242. This sensitive patient also felt all radiations from electrified bodies cold, especially those positively electrified, The conductor, glasses, and wood-work, all gave heat by themselves; as soon as I electrified them, and only to a strength capable of yielding positive sparks one-fifth of an inch long, and in the moist air of cloudy weather, she felt all these substances perfectly cold at distances of from ten to fifteen paces. This feeling of cold increased rapidly, the faster I turned the plate of the machine, yet was not immediate, but always became first perceptible several seconds later than the electric charge upon the bodies. A fox-skin, by itself warm, gave great cold, when I had beaten an electrophorus cake with it. The same occurred when I let the electricity flow from the conductor into the air through points, instead of electrifying bodies with extended surface.

When, on the other hand, I placed negatively electrified bodies opposite the observer, she found them warm; an electrophorus composed of pure resin, warm by itself, emitted far greater heat after it had been beaten with the fox-skin, and became observably warmer with almost every stroke, up to a certain degree, where it remained stationary.

After these observations the conclusion was warranted, that positively electrified bodies produced cold, negatively electrified warm sensations. Since this ran counter to the general ascertained theory, the cause of such effect must be derived from the electrical distribution, whereby the air, surrounding the positively electrified bodies in which the observer was placed, was negative by distribution, and consequently as the nearest substance must act negatively upon her sensations,-that is, in opposition to the condition of the electrified body.

243. A great number of experiments were made with the voltaic battery, and this would be the proper place to give an account of the temperature of the odic flames produced by it; but, as the results, on this point, appear too complicated to admit of dismissal with a passing notice, I must reserve the regular description of them for a special treatise.

244. The odic flames which were produced by candlelight, as by sun-light at the end of long wires, all felt cold. Miss Reichel felt the coolness of the odic-flames issuing from the further end of a long wire, twenty yards long, which was attached to a copper plate, illuminated by eight candles. Here, indeed, both heat and chemical action influenced. Sunlight, directed upon a large plate of iron, and thence turned towards her with the point of a wire, gave a flame of which the cooln€ ss reached very far; moonlight, on the contrary, thrown upon the same plate, produced heat in the flame at the point of the wire directed toward the observer; and this, always alike in many repetitions, at very different times.

245. The following experiment, similar to those in §§ 122 and 123, may indicate the condition of the Od produced by heat. With Miss Maix, I had an earthen pot filled with cold water, inserted a wire ten feet long into it, placed the other end in her hand, put a cover over the water, and allowed the patient to become accustomed to this arrangement. I then poured the cold out, and replaced it with boiling water. She at once felt the wire increase in apparent heat,-that is, in odic heat; this acquired a steady maximum in a few seconds. I now threw some pieces of ice into the boiling-hot water: the heat of the wire in the hand immediately began to decrease; it sank continually till it wholly disappeared, and now the temperature was reversed. The disagreeable heat of the wire vanished entirely, and in its place appeared the beginning of a coolness, which continually increased, and soon became very pleasant to the observer, affecting the hand, then by degrees the arm, and so on, the whole person, even to the back. Judging from this, I must assume that the warming produced positive, the cooling negative, movements of Od in the bodies.

246. Rubbing a copper plate with a piece of wood gave warm + od in the copper wire seven yards long, § 125.

247. The chemical polarization is usually decided by the predominant constituent, which enters into the compound, and in neutral combinations, by specific quality and position of these in the od-chemical series. A number of experiments, relating to this, have already been described in the fifth treatise, from tete 137, 139-142. I will add a few other instances here. I placed iron-filings in a glass cup, and poured some water on them. A glass rod inserted in this felt rather warm. I poured some vinegar in, and the rod at once gave cold. Vinegar, like almost all vegetable acids, is od-negative. But the rod soon became warm again; the vinegar had been neutralized by the iron, and a great excess of iron-filings remained. I then added citric acid: the same course was followed: in particular, after I had stirred up the mixture a little, the rod became wholly warm again. I next took, seriatim, a few other organic acids; all produced the same effect. In another experiment, I used strong solution of potass, as base, which, being od-positive, made the glass rod warm; sulphuric acid poured into this rendered it cold for a moment, then followed great heat, the alkali remaining in excess. Sulphuric acid added, to neutralization, produced warmth for some moments during the combination, but permanent cold followed; sulphate of potass, like all sulphuric acid salts, is an od-negative body. Effloresced carbonate of soda, placed in water, evinced at once an uncommon degree of cold; the imbibition of water of crystallization, in the place of that lost by efflorescence, was, therefore, an act expressing itself externally as negative. By stirring this, cold was increased for a short time, then it was moderated; carbonate of soda is itself od-negative. Addition of strong diluted sulphuric acid did not act upon the thermometer standing in the fluid, but the glass rod, nevertheless, became very warm during the evolution of carbonic acid: as soon as the effervescence ceased, it again became cold. Sulphate of soda is od-negative, but in the driving out and gasification of the carbonic acid, positive Od was necessarily set free. The observer often said that she felt the sensations like shocks during the decompositions; as the bubbles were formed, she fancied she felt reflex effect in the glass rod. We shall hereafter return to similar phenomena; for in these matters, there is nowhere effect without cause.

All chemical action, therefore, moves in manifold alternations of + and - od, dependent on the position of the substances entering into it, in the odic series; so that the result may always be predicted so soon as the relative value and quantity of these are known.

248. We now come to the examination of living organic structures: in the first place, of plants. I brought to Miss Maix some flower-pots, containing a Calla AEthiopica, a Pelargonium mosehatum, and an Aloe depressa. I rolled up one end of a long stout wire into several coils, and gave the other end into the hands of the patient, to allow her to get accustomed to it. I then laid the coils over the plants, so that these were surrounded and involved in them. An unexpected vivid effect displayed itself. The wire immediately became hot in the observer's hand, and this so much that it ran up the whole arm. At the same time, the point of the wire diffused cool wind. The Calla manifested the greatest strength, the Aloe the least; so that it seemed likely that the measure of the strength increases, in equal degrees, with the rapidity of growth of the plant. The quick growing Calla showed itself incomparably more active than the slow Aloe, in spite of its greater mass; while the Pelargonium moschatum always kept the medium. Perhaps the observation is not out of place here, that the Calla belongs to the family of the Aroidew, in which it is well known that the strongest evolutions of heat, therefore especial manifestations of intense vital activity, occur.

249. In the end of September, I walked in the fields with Miss Reichel. We noticed all the flowering plants we met with. Entire trees produced a total impression of coolness; single plants in pots, the same, collectively; in particular, however, she found most of them warm on the stem, but the flowers cool: e. g., in Gentiana ciliata, Inula salicina, Euphrasia officinalis, Odontitis lutea, Orobanche cruenla, Linum flavum, Hordeum distichums, Coronilla varia, Rosa Bengalensis, Pelargonium roseum, Iberis, Impatiens, Alchemilla, Campanula, Daucus, &c. Trees were also cold at the upper end, and warm near the ground: e.g., Pinus picea, Abies nigricans, Fraxinus excelsior, Hippophae rhamnoides, Laurus nobilis,Punica granatum, Quercus austriaca, Betula alba, Morus morettiana, Salisburia biloba, Hedera quinquefolia, Cassia corymbosa, Juglans regia, &c. Among the Composita., she found the ray-flowers of many cool, those of the disk warm,-e. g., Picris hieracioides, Centaurea paniculata, Aster sinensis, Amellus, Dahlia purpurea, Senecio elegans, Corcopsis bicolor, Asterocephalus ochroleucus, Scabiosa columbaria and atropurpurea, &c. Some were cool in the stem the inflorescence warm; as Plantago lanceolata and Salvia verticillata; she experienced a mixture of cold and heat from families of Clematis vitalba, and the capsules of Papaver somniferum where, indeed, she may have felt through the alkaloids and oil of the seed. It results from this, that different parts of different plants behave diffirently in relation to Od.

250. To come closer to the facts, I pulled up a large turnip, and made Miss Reichel examine it. She found the fibrils of the root od-positive, but the tuber od-negative below, and od-positive above; the whole head of the thickened tap-root, especially the neck, where the buds and leaves are produced, very warm; all the leaves warm at the base, slightly warm at the points, but above the middle zone, where they are most widely expanded, very cold. A plant of Heracleum sphondylium, as high as a man, had the root warm, the stem, up to immediately below the umbel, warm, round the involucre still warmer, the umbel itself cold. A ripe cucumber and a melon were found cool above, on the remains of the flower, but cold below at the point of attachment to the stem.

251. Hence it followed, that no universal polarization in regard to Od, according in any way with Caudex ascendens and descendens, somewhat as in crystals, occurs in plants, but that positive and negative conditions alternate at different points: however, internodes of the same name, and within these, again, parts of the same name, possessed like odic disposition: I therefore turned to the investigation of the single organs. First, with Miss Maix, on a young Aloe depressa. She found the point of the main axis strongest; on the other hand, in detail, the larger, lower leaves acting more strongly,-that is, diffusing more cold wind than the smaller upper ones; stronger in the axils than at the points; the mid-ribs, with their vascular bundles, stronger than the rest of the parenchymatous mass; lastly, the under surface of the leaves stronger than the upper. The same plant, as well as an Agave Americana, when gone through with Miss Reichel, gave the same results: the little stein cooler at the apex, than at the base; each leaf stronger at the base and on the under face, than at the point and upper face, and the mid-rib stronger than the borders and parenchyma. The two plants were of about equal size, and bore from ten to twelve leaves. A leaf of Ulmus campestris, of Latin's nobilis, and of Punica granatum, all still upon the tree, were each wanner on the under face than on the upper; and again, warmer at the point of attachment than at the tip. Leaves of Castanea vesca, taken from the tree, were compared in three different stages of growths,-when green, when become yellow, and when wintery brown; in all of which conditions they could be obtained in October. The green and yellow acted in general as cooling to the hands of the sensitive,-the green stronger, the yellow weaker, the brown not at all, and behaved, like a sheet of paper, almost indifferently, with a slight indication of tepid warmth.

252. The general results of the experiments on vegetation, so far as they have been thus made in a preliminary manner, would, therefore, allow of our summing them up as follows:-The root-fibres are warm, therefore od-positive; the ends of the leaves, above, are cold, therefore od-negative. The point of the stem loses itself in leaves and leaf-buds; it therefore comes to the negative side. We may say, then, with some grounds, positive Od predominates in the descending axis; negative Od in the ascending. This must, however, be accepted with great limitation; for innumerable individual conditions prevailed within these principal states, an infinitely distributed duplicity, in which + and - od alternate a thousand times. The rule peeped forth, however, here, that where nature is least busy,-where the growing activity is slackened, negativity prevails,-where propulsion shows itself; positivity. Thus the vascular bundles in the mid-ribs, the under face of the leaves, and the lower part of the leaves toward the point of attachment, were always found more positive; while the more parenchymatous mass, the upper face of the leaves, and the part toward the tip, were constantly more negative. Physiology teaches us that the leaf does not grow principally at the point, but toward the point of attachment, that the apex is perfect very soon after it emerges from the bud; while at the stem end,-that is, the lower half,- the leaf continues to grow for a long time.5 The vegetative propulsion, therefore, soon ceases in front, but remains active behind. Here, then, it appears that it is in league with positivity of the imponderables, light, heat, and Od, that creative nature erects her structure; and when she gives up the field to negativity, she carries away life with her in her retreat.

253. We have still to direct our view to the animal kingdom. How immeasurably great the part is which Od here plays, is best shewn us by the profound and enigmatical phenomena of somnambulism. The question, however, here, is not of this, but of certain reactions of healthy life upon the sensitive. When I placed a living animal upon a copper plate, connected by a copper wire several yards long, with Miss Maix's hand, though it was very small-for instance, a rose-beetle (Cetonia aurata) or a moth (Bansbyx mori), or any similar creature,-I was astonished to perceive that she instantly recognized this, after a few seconds, by the apparent temperature of the wire, whether she saw it or not. When I placed a larger animal on it, such as a cat, she felt it very vividly. The effect of my own hand, when I placed it upon the plate, spread all over this, as has been already detailed in other places. I have examined the reactions countless times, in hundreds of modifications; they gave the always a constant result, that every living creature at once propagates an influence, not only immediately, but even mediately, through various kinds of bodies and long wires, which Miss Maix found as warmth, diffusing at the same time a cool wind, like all the od-diffusing objects of inorganic nature. When I removed the animals, the effect soon ceased, and the wire sank back to its natural peculiar temperature. I made similar experiments with beetles, moths, and cats, on Miss Reichel, which confirmed the preceding in all their results.

254. When I elevated my hands towards Miss Reichel, she felt, even at a distance, warmth flow to her from my left, and coolness from my right hand, as from a distant magnet. Miss Atzmannsdorfer felt the same still more strongly. When I approached Miss Reichel sideways, so that I only turned my right side to her, she felt coolness from me as soon as I came in at the door of the room; when I came forward with my left side, she felt me warm. Not only the hands, but the whole sides of human beings, are, left od-positive, right od-negative. Next to the hands, she found the head especially strongly odic, on the right side negative, on the left positive. The toes were in the same way greatly strengthened. With regard to front and back, the front of the head was always found cooler, the back of the head warmer down towards the neck. In the arms and hand, both she and Misses Maix and Nowotny found the following arrangement. The tips of the fingers were the strongest; then followed those parts of the hands where the fingers arise; then the tendinous part, at the wrist, i. e. where the hand is attached inside to the fore arm; lastly, the parts of the inside of the upper arm, to which the fore-arm joins. In the fingers themselves, again, there were places of different amounts of sensibility; but in all places where a finger-joint ended downwards, it lay inside. Nature, therefore, evidently proceeds according to the following rule here. From the shoulder to the tips of the fingers, the point of greatest irritability, in every joint, always lies on the inside at the distal end of the joint. There are, consequently, six places from the shoulder to the fore arm increasing in sensibility downwards; the lower end of the upper arm, of the fore arm, of the hand, of the joints of the fingers, always lying in the inside: on the outside there is no especially sensitive point.

255. The mouth, with the tongue, is a point of very peculiar strength. It is very cool; that is, od-negative. The sensitive feel all that they touch with the mouth with especial distinctness and strength in reference to its odic value; on the other hand, the mouth of the healthy is a point from which all objects can be charged more strongly, odically, than with the hands. When I held a glass tube, a metallic tube, a silver spoon, a wooden stick, &c., in my mouth, and let the various sensitives feel the other end; they all found them very strongly odified. When I put a glass of water to my mouth, as if I had intended to drink, and then after a short time gave it to the sensitive patient, she took it for magnetized water. When I passed my mouth, closed and without breathing, along the German-silver conductor, without touching it, keeping my mouth only about a minute very close to it, and then allowed Misses Maix, Reichel, Atzmannsdorfer, or Sturniann to grasp it, they found it as perfectly charged as if it had been in contact with a magnet, the sun's rays, the point of a crystal, or my bands.

We here arrive at a not uninteresting explanation of a hitherto obscure matter-the import of the kiss, The lips form one of the foci of the biod, and the flames which our poets describe, do actually blaze there. This will be clearly elucidated in the next treatise.

It may be asked, how this can agree with the circumstance that the month is od-negative? This, however, does harmonize very well with the fact; for the kiss gives nothing, it desires and strives merely, it sucks in and sips, and while it revels, longing and desire increase. The kiss is therefore not a negation, but a physical and moral negativity.

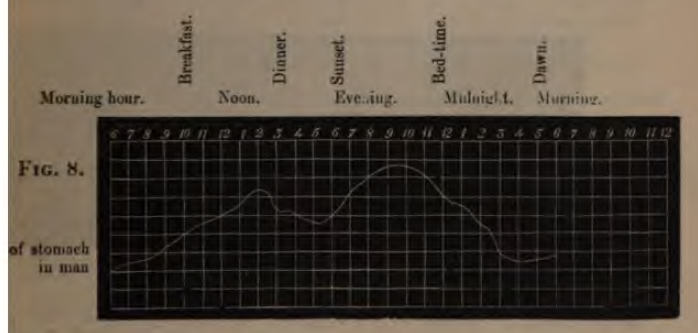

256. As the Od is unequally distributed in space over the human body, so also, l concluded, will it deport itself in time. I conjectured from many reasons, that the Od might. change its distribution, and displace its relative intensities, in the different bodily and mental conditions which we pass through in the twenty-four hours. If such a guess should prove, from experiment, to be well grounded, 1 hoped we might gain highly interesting hints, even if not explanation, of sleep, digestion, hunger, growing hot., chilling, the mental changes in their physical effects, and so on as to the questions bordering on physics. And if, in the first instance only, inconsiderable data could be discovered in this way, it would certainly indicate to us a new and promising direction

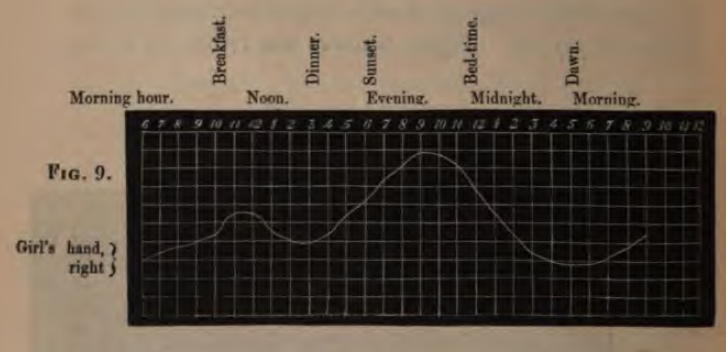

for the investigation of things which are, in all respects, so difficult to throw light upon. With this view, I commenced by letting Miss Reichel make hourly observations on myself, and representing these by graphic lines, in which the times were expressed by the abscisses, and the strength of the Od by the ordinates. I completed the investigations on myself, on my daughter H., and on Miss Reichel herself. A period occurred to the last, in which she remained perfectly sleepless for three weeks, and I availed myself of this time for carrying on the testings, through the night, without interruption. They were arranged in this way: my right hand was grasped by the sensitive every hour, and tested for its strength at that time, measured, and then the point marked upon the table, which proportionately corresponded to the condition of force found. This was continued for twelve, eighteen, to twenty-six hours, in various experiments. My usual habit of life during this was, to wake at from 6 to 7 in the morning, to read in bed till 9-10, rise, and breakfast on cold weak tea at 11-12, dine at 3 P.M., to eat a very little confectionary at 10 P.M., and go to bed between 11 and 12. I drank neither wine nor beer, toast and water, coffee, nor tea, and did not smoke. I took no exercise beyond a moderate walk, which did not extend further than through the park of the castle; and I passed my time, chiefly, quietly at the reading-desk. In other respects, I was in good health, tranquil frame of mind, and at the age of fifty-six. So much for the circumstances which might have had influence on the experiments. In all cases, I avoided touching with my hand every metallic object, even the lock of the door, which I let others open for me, for a quarter of an hour before the trial of the feeling; after meals, when I had used silver instruments, I always let some time elapse before I gave my hand to be examined I also avoided allowing the sun's rays to fall upon me, or going near the fire.

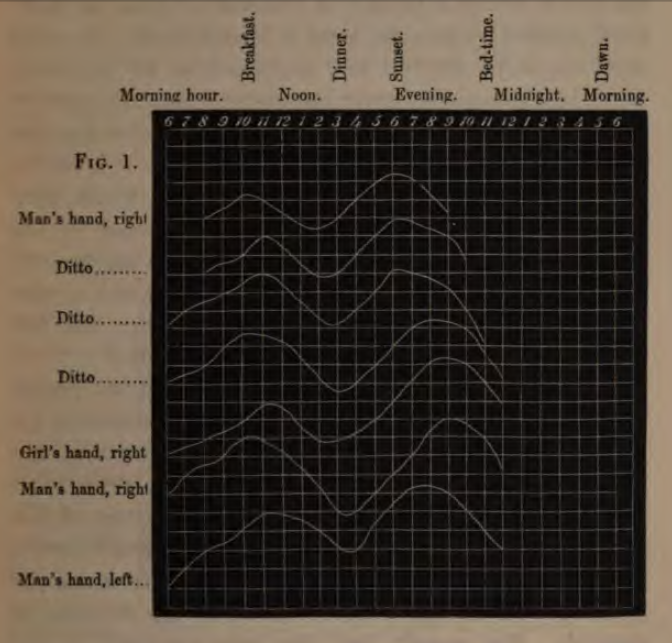

257. Since the standard which could be taken depended merely upon feeling, that is, upon the appreciation of a sensation, which could not be controlled by any scale, it can only lay claim to a moderate amount of accuracy. To approach as nearly to the truth, as was possible, under such circumstances, I repeated the same experiments five or six times; those, namely, in which I let my hand be felt, and marked duwn the result, hourly, from the morning till late at night. This operation is illustrated in fig. 1, and the various results collocated. The agreement which is found between the various series of observations is almost astonishing, and proves that the sense of feeling of the observer, as I have already frequently noticed, possessed a very high degree of clearness.

As soon as I attained conviction from this, that observations of conformable conditions could really be obtained in this way, I extended the operation in various directions. I continued them through the night, had them made by females, among others by the observer on herself, &c. I then caused the particular organs of one and the same person to be investigated, and finally, the similar organs of the same persons to be compared with each other.

258. We will bring to light the particulars of this. In the first figure are a number of observations upon my right hand, marked by the right hand of Miss Reichel. My right is, of course, od-negative, and continued so for the whole time, since this quality never does alter. But the quantity of it does change, and is subject to a continual rising and falling. I call this the magnitude of the force. It is shown in the drawing, that from 6 A.M. forward, at which time the observation mostly began, a growing increase of the force occurred, till the hours of 10 or 12. Then commenced a decline, going on till 3 P.M. From here started a new ascent, and it became greater until 7 to 9 P.M.; then followed a continual decrease until late in the night.

This plate, with its often-repeated observations, proves that from the time of awaking, although I remained for hours reading in bed, the Od increased in strength in my right hand, growing greater continually after breakfast until toward noon. The rising day, therefore, strengthened the hand. The decline which now appeared, endured exactly till dinner-time, and it hence became evident, that it was the awakening of hunger which brought on the decrease of strength. For scarcely had this been appeased by the dinner, when, with the first spoonful of warm soup, the decline ceased, and the force immediately began to rise, and so on to its maximum, which was attained in the evening at the time of the departure of daylight. Similar experiments with Miss Mix and M. Schuh yielded similar results; both found my hands to influence them more powerfully after inner than before.

There will be observed on the diagram a slight tendency to decline about 9 or 10 A.N. This relates clearly to the breakfast, the desire for which then arises; this case is an appendix to the greater decline before dinner, and serves to corroborate it.

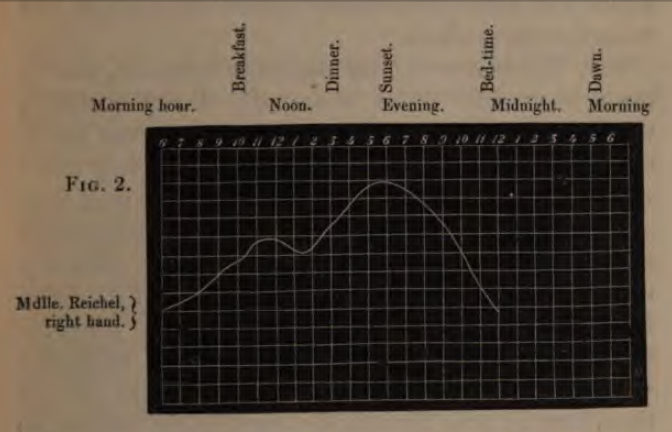

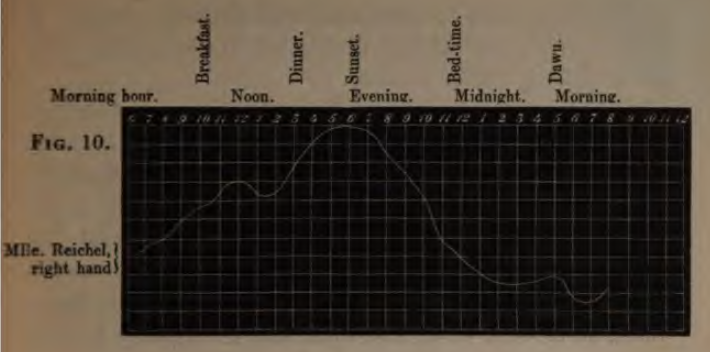

259. In order to make certain of the correctness of the view which I had formed on these points, I caused the ex- periments to be performed by a person who took meals at ditlerent times of the day. Miss Reichel herself dined at my house at 1 o'clock instead of 3. She could observe her own right hand very well with her left, and so undertook this task. A wholly different line was now formed. (Fig. 2.)

The same increase of the force appeared generally from morning to noon; its decline, however, which also cotnmenced now, did not endure till 3 o'clock, but extended only till 1, the hour of her dinner-time, and then ceased at once, to make way for a new ascent of the odic force, which then continued to increase for exactly the same time, and reached its culmination, when the day began to disappear. A little decline was also observable with her at the period before breakfast, which gave place to an increase directly she had taken the meal.

260. From these comparative experiments it follows, therefore, that hunger diminishes the strength of the Od in the right hand; taking food increases it. We here clearly come upon the effects of chemism, as they have been elucidated in the fifth of these treatises. The food received becomes the prey of chemical force; digestion, that is, decomposition, begins, and odic action is produced; chymod becomes free, if we like so to express it. It makes no difference whatever, how much or how little share may be attributed or denied to vitality, in these decompositions,- decompositions they remain, and from them arise manifestations of Od, which diffuse themselves over the organism, and strengthen its members.

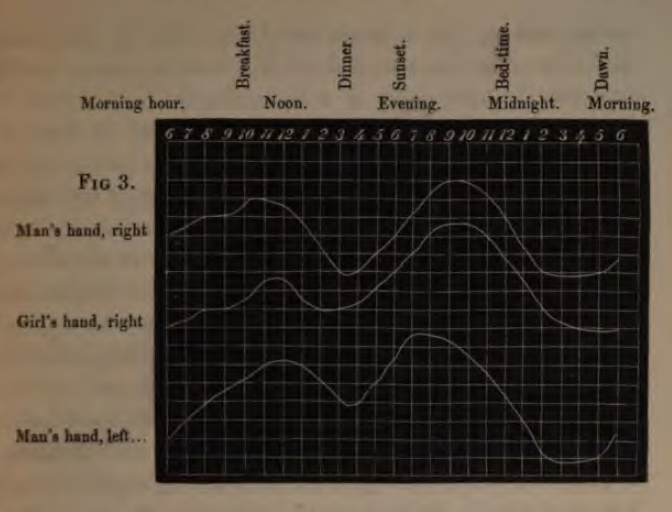

261. The question of the day being answered, that of the night remains. What is our odic disposition during the time when the luminary of the day, with its vast source of Od, is wanting, and the powerful influence of sleep comes over us? To investigate this, the sick observer must keep awake, and the healthy subject sleep, and the examination must be continued hour by hour; so that the affair was clearly not without its difficulties. However, I succeeded in persuading Miss Reichel, by explaining to her the scientific value of such an investigation, and the undoubted merit attaching to her for it, to come, since she did not sleep, hour by hour through the night to my bedside, to examine the condition of my hand, and note the result. There was no other means, since, in order to obtain a true result, it was indispensable that I should lie and sleep in my usual bed, as on other nights. Fig. 3 shows the result of various modified observations on myself and other persons. From the morning forward, the Od increased on my right hand, some interruptions through hunger being left out of view, through the whole day till at least 6 o'clock in the evening, at latest till 9. It now most distinctly turned, and fell continually till 2 or 3 A.M., when it attained a stable minimum, which endured to break of day; at the time of the experiment about 5 to 6 o'clock. Then, however, as the grey dawn drove away the darkness, the force was at once aroused, and fresh life reinforced the organic world; Od and vital force increased anew throughout the whole day as long as the sun sent down rays from heaven.

262. Here, also, I was permitted to find confirmation of a law discovered earlier in a different way. The sun, the one great source of Od, sends it to us with light and heat, and thus, throughout the whole day, imbues with it all that it shines upon, Directly the sun sinks below the horizon, the odic tension sinks in the human organs, and with commencement of this change comes also to living human beings, weariness, dulness of the senses, and sleep. When the od-spring of day ceases to flow, the fountain of conscious waking life becomes dried up. Not by light and

heat alone does the sun call all life into existence, but it uses another potentiality as a lever, the Od, with which it impenetrates all things, even as with heat, and the fluctuations of which we are now beginning to learn how to compare and measure with the conditions of sleeping and waking. That it makes little difference here, in general, whether the sun's rays fall upon us directly, or we are in the shade,

follows from the law of conductibility and distribution, as

we have already learned; and wherever we may be, a proportionate share of the Od which the day brings will fall upon us.

263. But what are the conditions of the left hand here, which is oppositely polar? Will it increase and decrease

in positivity in the same proportion as the right gained and lost negativity? This can only be made out by making both hands the subjects of observation simultaneously, and, noting

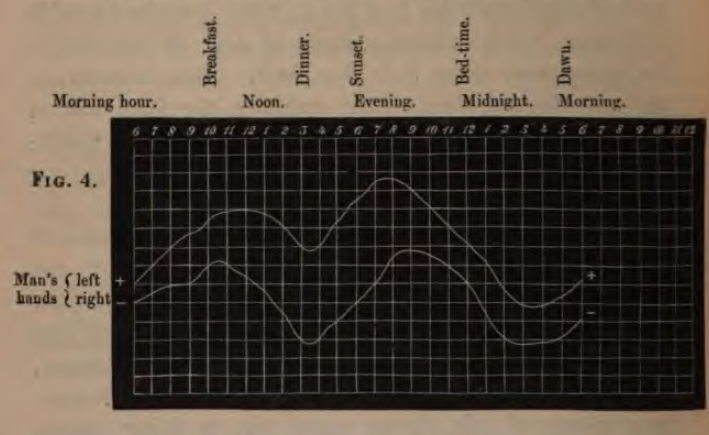

down their odic condition at the same time. Fig. 4 shows how this was carried out.

The lower line shows the course of the negative right hand, the upper that of the positive left. This latter exhibits a more rapid increase of

positive od in the morning, and again a higher elevation in the afternoon, till 7 o'clock, than the negative right. The midday hunger period does not show so deep a decline as in the right. It makes the smaller maximum, at mid-day, somewhat later, the evening one somewhat earlier, than the right. It appears to correspond to a greater energy of development of Od.

The od-positive left hand, therefore, does not follow exactly the same, but still a very similar odic course, with the od-negative right, taken in the protensive point of view (in regard to changes of tension.-ED.)

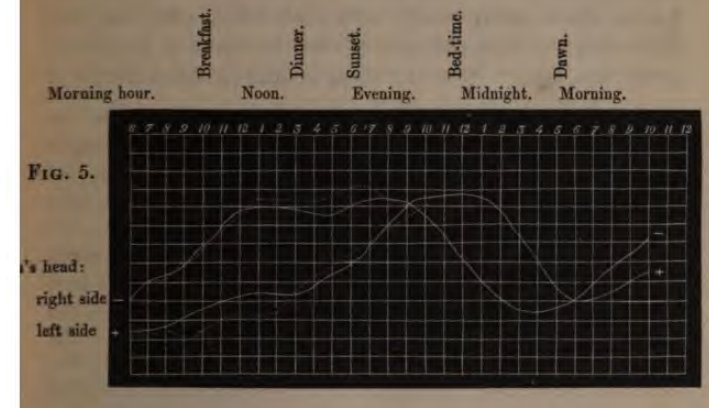

264. The brain has so symmetrical a structure that when such great inner differences appeared in the symmetrical hands as to form a perfect contrast, I could not but reflect on the deeper lying mechanism of human beings, of which the hands are but the outstretched levers. The brain, which many try, not always very happily, to plan out according to its bony shell,6 might it not, perchance, be also gifted and imbued with the delicate potentiality of Od, and make itself as perceptible to such delicate reagents as our sensitives are? Miss Reichel found the right side of my skull cool, exactly like my right hand, but much stronger, while the left side was warm. This was the case, not only in me, but in all other persons whom I subjected to the investigation, male and female, all alike. I may especially mention M. Th. Kotschy, who allowed Miss Reichel to make an accurate examination, and whose head, sides, and hands, she found to agree exactly qualitatively with mine. This appeared to me really much more worthy of a funds. mental examination than the hands could be, and therefore I repeated the 24 hours' inquiry on two different days and nights, on the 18th and the 23d of October, 1844. Fig. 5 shows the course, the continuous line indicates the path of the first investigation, the dotted of the second, which could only be carried to 10 o'clock in the evening.

265. This operation furnished remarkable acquisitions. It showed that as an unequal course occurred at the same times in the hands, so, also, did it to a far greater extent in the two sides of the brain. The left side increased in strength much more slowly than the right in the morning; till toward 3 o'clock, it was scarcely of importance; while the right had already attained its first maximum at 1 o'clock, which was scarcely inferior to that it attained in the evening.

The weakness from hunger, before dinner, existed on both sides, but far smaller than it showed itself in the hands. While the right side advanced almost on a level till 9 o'clock, the left rose unceasingly from 3 till 11 P.m. The right began to sink already about 8 P.m., to cross the left and fall deep below it, while the left did not begin to descend from its culmination till i A.M.; that is, five hours later. The morning rise was, however, almost simultaneous.

The conclusions to be drawn from this, are: the course of the brain is, on the whole, analogous to that of the head: increase in the morning; at noon, a temporary decline; upper culmination in the evening, and lower culmination about 4 A.M., agree pretty nearly with each other, and thus probably with the daily course of the whole organism, in a mode of life like mine. But the brain exhibits a difference from the hands, in the far smaller participation in the influence from hunger, and the satiation of the stomach. The organs of the understanding and soul appear to take less notice of the crude nutrient operations, than the matter-ruling hands.7

In fact, nature has done well to provide that the forces of the soul, pre-occupied with cares, should not decline immediately that food is wanting. The difference of the two sides of the brain between themselves, shows us that the right side inclines to sleep much earlier than the left, as well as rises to the strongest animation much earlier in the morning than the latter: therefore, betrays generally a greater excitability, but not greater strength, than the left.

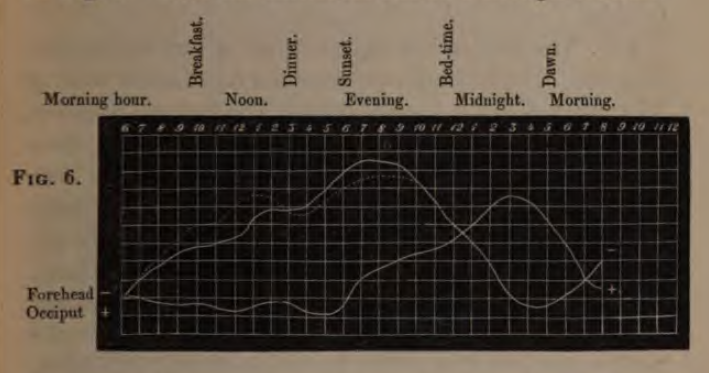

266. The fore and hind parts of the head are more different, anatomically, than the right and left sides of the brain, and I was desirous of bringing this opposition also to the test of the present researches. This operation was also performed twice, on the 10th and '2 Oth of October, each time through twenty-four consecutive hours, and it is expressed 'n Fig. 6. Here the differences offered a stronger contrast.

The forehead in general manifested cold, the back of the head considerable beat, and this not only in men, but in animals; it occurred so in the house-cat, and when from the hint this afforded, I led the observer to my stables, she found it also in the horses and cows, especially a strong warmth in the hollow of the neck of the last. The forehead of human beings became in like manner greatly exalted in the morning, with the dawning of day, took hut small share in the effects of the matutinal and mid-day periods of hunger, and reached its culmination after sunset. During the whole of this time the back of the head remained almost unchanged, so that at six o'clock iu the evening it was exactly in the same place as at six o'clock in the morning. But then it suddenly arose.. almost at the same time that the forehead began to enter upon its retrograde course.

From this point forward, they are seen to cross diagonally, and while the back of the head continually rises until 3 A.M., the forehead falls incessantly till about the same hour; the one to reach its upper, the other its lower culmination, almost at the same moment. From this point, again, the opposite course commenced, and while, after three o'clock, the exalted back of the head full rapidly, toward 4 o'clock the deeply depressed forehead began in like manner to rise quickly.

267. This motion is a representation of our waking and sleeping. The forehead represents the functions of waking life; the back of the head, of sleep. The forehead advances with increasing odic invigoration and operative activity, from 5 in the morning, with break of dawn, to sunset; then it loses the ad-spring of the luminary of the day, and sinks again incessantly from its height., until the new day begins to break, when the force conies anew to rejoin it. The back of the head, on the contrary, passes quietly through the whole day, almost without motion; but so soon as the sun has sunk below the horizon, the hour of its nightly labour has struck. Now arises the Morpheus, and with rapid steps he advances, until the first traces of morning's light remind him the forehead is on its way to free hint from his work; the back of the head sinks from its greatest to its lowest elevation, at. the close of night, just as rapidly and uninterruptedly as the forehead sunk from its, at the close of day. Thus the two not only shew themselves opposed in polarity, -since one is warm, that is nd-positive, and the other cold, consequently od-negative,- but they are as diametrically opposed to each other in their operations as are day and night, waking and sleeping.

268. From this comparison it is seen, that between waking and sleeping, in relation to Od at least, there is not in opposition like that between activity and rest, like that between motion and stillness; but only that the focus of activity is changed. The force does not cease to act; it does not diminish, but it removes merely from the front of the brain to the back, and in proportion as the front gives up intensity, the back seizes it. Sleep thus declares itself, not as a decline of the vital activity, but only as a displacement of it. In just the same measure as the vital force is active in the forehead in the day, does it rule in the hinder part of the head during night. Sleep, therefore, is only an alternation in the functions of our organs and powers; in no way an introduction of any kind to a state of rest of them; and the poets may use the comparison of sleep with death as a metaphor, but the physiologist cannot, in the consideration of organic life.8 Vitality is exactly as energetically r active in another direction during sleep, as in the waking condition. The business of sleep is governed by the cerebellum: while the forehead suspends its mental labour, and when it takes to it again, to which it is aroused and quali. fled by the radiations of the sun, the back of the head lowers its claims upon the vital force.

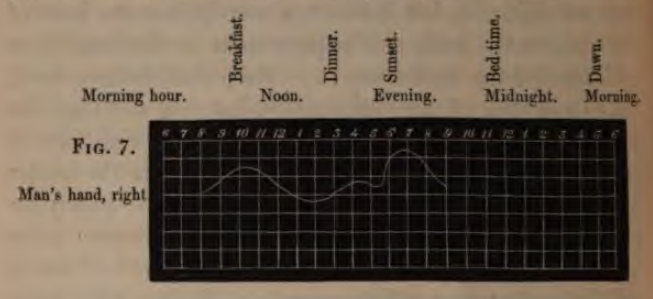

A small accessory, but yet not contemptible support to this, is afforded also by Fig. 7.

I had become sleepy soon after dinner, and resting my head on the back of my chair, I slept for ten minutes. During this, and shortly before and after, the sensitive observer felt my right hand. The result is shown in the diagram, marked distinctly between four and five o'clock. While on all other days, the force increased continually during this time, it here made an anomalous leap downward, but then rose again normally. Therefore, the short sleep into which I had fallen bad sufficed to produce a very perceptible change in the distribution of the Od in me; as long as it endured, the manifestation of odic force in the hand rapidly diminished; the ordinate of the force was shortened, and then increased again when I awoke, and all the vital functions again t up their previous directions.